Prostatitis: Inflammation of the Prostate

On this page:

- What is prostatitis?

- What is the prostate?

- What causes prostatitis?

- How common is prostatitis?

- Who is more likely to develop prostatitis?

- What are the symptoms of prostatitis?

- What are the complications of prostatitis?

- When to Seek Medical Care

- How is prostatitis diagnosed?

- How is prostatitis treated?

- How can prostatitis be prevented?

- Eating, Diet, and Nutrition

- Clinical Trials

What is prostatitis?

Prostatitis is a frequently painful condition that involves inflammation of the prostate and sometimes the areas around the prostate.

Scientists have identified four types of prostatitis:

- chronic prostatitis or chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- acute bacterial prostatitis

- chronic bacterial prostatitis

- asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis

Men with asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis do not have symptoms. A health care provider may diagnose asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis when testing for other urinary tract or reproductive tract disorders. This type of prostatitis does not cause complications and does not need treatment.

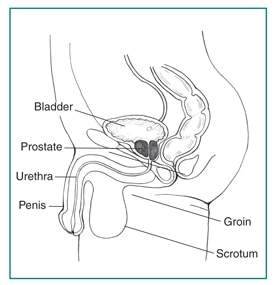

What is the prostate?

The prostate is a walnut-shaped gland that is part of the male reproductive system. The main function of the prostate is to make a fluid that goes into semen. Prostate fluid is essential for a man’s fertility. The gland surrounds the urethra at the neck of the bladder. The bladder neck is the area where the urethra joins the bladder. The bladder and urethra are parts of the lower urinary tract. The prostate has two or more lobes, or sections, enclosed by an outer layer of tissue, and it is in front of the rectum, just below the bladder. The urethra is the tube that carries urine from the bladder to the outside of the body. In men, the urethra also carries semen out through the penis.

What causes prostatitis?

The causes of prostatitis differ depending on the type.

Chronic prostatitis or chronic pelvic pain syndrome. The exact cause of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome is unknown. Researchers believe a microorganism, though not a bacterial infection, may cause the condition. This type of prostatitis may relate to chemicals in the urine, the immune system’s response to a previous urinary tract infection (UTI), or nerve damage in the pelvic area.

Acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis. A bacterial infection of the prostate causes bacterial prostatitis. The acute type happens suddenly and lasts a short time, while the chronic type develops slowly and lasts a long time, often years. The infection may occur when bacteria travel from the urethra into the prostate.

How common is prostatitis?

Prostatitis is the most common urinary tract problem for men younger than age 50 and the third most common urinary tract problem for men older than age 50.1 Prostatitis accounts for about two million visits to health care providers in the United States each year.2

Chronic prostatitis or chronic pelvic pain syndrome is

- the most common and least understood form of prostatitis.

- can occur in men of any age group.

- affects 10 to 15 percent of the U.S. male population.3

Who is more likely to develop prostatitis?

The factors that affect a man’s chances of developing prostatitis differ depending on the type.

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Men with nerve damage in the lower urinary tract due to surgery or trauma may be more likely to develop chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Psychological stress may also increase a man’s chances of developing the condition.

Acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis. Men with lower UTIs may be more likely to develop bacterial prostatitis. UTIs that recur or are difficult to treat may lead to chronic bacterial prostatitis.

What are the symptoms of prostatitis?

Each type of prostatitis has a range of symptoms that vary depending on the cause and may not be the same for every man. Many symptoms are similar to those of other conditions.

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. The main symptoms of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome can include pain or discomfort lasting 3 or more months in one or more of the following areas:

- between the scrotum and anus

- the central lower abdomen

- the penis

- the scrotum

- the lower back

Pain during or after ejaculation is another common symptom. A man with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome may have pain spread out around the pelvic area or may have pain in one or more areas at the same time. The pain may come and go and appear suddenly or gradually. Other symptoms may include

- pain in the urethra during or after urination.

- pain in the penis during or after urination.

- urinary frequency—urination eight or more times a day. The bladder begins to contract even when it contains small amounts of urine, causing more frequent urination.

- urinary urgency—the inability to delay urination.

- a weak or an interrupted urine stream.

Acute bacterial prostatitis. The symptoms of acute bacterial prostatitis come on suddenly and are severe. Men should seek immediate medical care. Symptoms of acute bacterial prostatitis may include

- urinary frequency

- urinary urgency

- fever

- chills

- a burning feeling or pain during urination

- pain in the genital area, groin, lower abdomen, or lower back

- nocturia—frequent urination during periods of sleep

- nausea and vomiting

- body aches

- urinary retention—the inability to empty the bladder completely

- trouble starting a urine stream

- a weak or an interrupted urine stream

- urinary blockage—the complete inability to urinate

- a UTI—as shown by bacteria and infection-fighting cells in the urine

Chronic bacterial prostatitis. The symptoms of chronic bacterial prostatitis are similar to those of acute bacterial prostatitis, though not as severe. This type of prostatitis often develops slowly and can last 3 or more months. The symptoms may come and go, or they may be mild all the time. Chronic bacterial prostatitis may occur after previous treatment of acute bacterial prostatitis or a UTI. The symptoms of chronic bacterial prostatitis may include

- urinary frequency

- urinary urgency

- a burning feeling or pain during urination

- pain in the genital area, groin, lower abdomen, or lower back

- nocturia

- painful ejaculation

- urinary retention

- trouble starting a urine stream

- a weak or an interrupted urine stream

- urinary blockage

- a UTI

What are the complications of prostatitis?

The complications of prostatitis may include

- bacterial infection in the bloodstream

- prostatic abscess—a pus-filled cavity in the prostate

- sexual dysfunction

- inflammation of reproductive organs near the prostate

How is prostatitis diagnosed?

A health care provider diagnoses prostatitis based on

- a personal and family medical history

- a physical exam

- medical tests

A health care provider may have to rule out other conditions that cause similar signs and symptoms before diagnosing prostatitis.

Personal and Family Medical History

Taking a personal and family medical history is one of the first things a health care provider may do to help diagnose prostatitis.

Physical Exam

A physical exam may help diagnose prostatitis. During a physical exam, a health care provider usually

- examines a patient’s body, which can include checking for

- discharge from the urethra

- enlarged or tender lymph nodes in the groin

- a swollen or tender scrotum

- performs a digital rectal exam

A digital rectal exam, or rectal exam, is a physical exam of the prostate. To perform the exam, the health care provider asks the man to bend over a table or lie on his side while holding his knees close to his chest. The health care provider slides a gloved, lubricated finger into the rectum and feels the part of the prostate that lies next to the rectum. The man may feel slight, brief discomfort during the rectal exam. A health care provider usually performs a rectal exam during an office visit, and the man does not need anesthesia. The exam helps the health care provider see if the prostate is enlarged or tender or has any abnormalities that require more testing.

Many health care providers perform a rectal exam as part of a routine physical exam for men age 40 or older, whether or not they have urinary problems.

During a digital rectal exam, your health care professional slides a gloved, lubricated finger into your rectum and feels your prostate.

During a digital rectal exam, your health care professional slides a gloved, lubricated finger into your rectum and feels your prostate.

Medical Tests

A health care provider may refer men to a urologist—a doctor who specializes in the urinary tract and male reproductive system. A urologist uses medical tests to help diagnose lower urinary tract problems related to prostatitis and recommend treatment. Medical tests may include

- urinalysis

- blood tests

- urodynamic tests

- cystoscopy

- transrectal ultrasound

- biopsy

- semen analysis

Urinalysis. Urinalysis involves testing a urine sample. The patient collects a urine sample in a special container in a health care provider’s office or a commercial facility. A health care provider tests the sample during an office visit or sends it to a lab for analysis. For the test, a nurse or technician places a strip of chemically treated paper, called a dipstick, into the urine. Patches on the dipstick change color to indicate signs of infection in urine.

The health care provider can diagnose the bacterial forms of prostatitis by examining the urine sample with a microscope. The health care provider may also send the sample to a lab to perform a culture. In a urine culture, a lab technician places some of the urine sample in a tube or dish with a substance that encourages any bacteria present to grow; once the bacteria have multiplied, a technician can identify them.

Blood tests. Blood tests involve a health care provider drawing blood during an office visit or in a commercial facility and sending the sample to a lab for analysis. Blood tests can show signs of infection and other prostate problems, such as prostate cancer.

Urodynamic tests. Urodynamic tests include a variety of procedures that look at how well the bladder and urethra store and release urine. A health care provider performs urodynamic tests during an office visit or in an outpatient center or a hospital. Some urodynamic tests do not require anesthesia; others may require local anesthesia. Most urodynamic tests focus on the bladder’s ability to hold urine and empty steadily and completely and may include the following:

- uroflowmetry, which measures how rapidly the bladder releases urine

- postvoid residual measurement, which evaluates how much urine remains in the bladder after urination

Cystoscopy. Cystoscopy is a procedure that uses a tubelike instrument, called a cystoscope, to look inside the urethra and bladder. A urologist inserts the cystoscope through the opening at the tip of the penis and into the lower urinary tract. He or she performs cystoscopy during an office visit or in an outpatient center or a hospital. He or she will give the patient local anesthesia. In some cases, the patient may require sedation and regional or general anesthesia. A urologist may use cystoscopy to look for narrowing, blockage, or stones in the urinary tract.

Transrectal ultrasound. Transrectal ultrasound uses a device, called a transducer, that bounces safe, painless sound waves off organs to create an image of their structure. The health care provider can move the transducer to different angles to make it possible to examine different organs. A specially trained technician performs the procedure in a health care provider’s office, an outpatient center, or a hospital, and a radiologist—a doctor who specializes in medical imaging—interprets the images; the patient does not require anesthesia. Urologists most often use transrectal ultrasound to examine the prostate. In a transrectal ultrasound, the technician inserts a transducer slightly larger than a pen into the man’s rectum next to the prostate. The ultrasound image shows the size of the prostate and any abnormalities, such as tumors. Transrectal ultrasound cannot reliably diagnose prostate cancer.

Biopsy. Biopsy is a procedure that involves taking a small piece of prostate tissue for examination with a microscope. A urologist performs the biopsy in an outpatient center or a hospital. He or she will give the patient light sedation and local anesthetic; however, in some cases, the patient will require general anesthesia. The urologist uses imaging techniques such as ultrasound, a computerized tomography scan, or magnetic resonance imaging to guide the biopsy needle into the prostate. A pathologist—a doctor who specializes in examining tissues to diagnose diseases—examines the prostate tissue in a lab. The test can show whether prostate cancer is present.

Semen analysis. Semen analysis is a test to measure the amount and quality of a man’s semen and sperm. The man collects a semen sample in a special container at home, a health care provider’s office, or a commercial facility. A health care provider analyzes the sample during an office visit or sends it to a lab for analysis. A semen sample can show blood and signs of infection.

How is prostatitis treated?

Treatment depends on the type of prostatitis.

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Treatment for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome aims to decrease pain, discomfort, and inflammation. A wide range of symptoms exists and no single treatment works for every man. Although antibiotics will not help treat nonbacterial prostatitis, a urologist may prescribe them, at least initially, until the urologist can rule out a bacterial infection. A urologist may prescribe other medications:

- silodosin (Rapaflo)

- 5-alpha reductase inhibitors such as finasteride (Proscar) and dutasteride (Avodart)

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs—also called NSAIDs—such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen sodium

- glycosaminogly

- CANS such as chondroitin sulfate

- muscle relaxants such as cyclobenzaprine (Amrix, Flexeril) and clonazepam (Klonopin)

- neuromodulators such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline (Aventyl, Pamelor), and pregabalin (Lyrica)

Alternative treatments may include

- warm baths, called sitz baths

- local heat therapy with hot water bottles or heating pads

- physical therapy, such as

- Kegel exercises—tightening and relaxing the muscles that hold urine in the bladder and hold the bladder in its proper position. Also called pelvic muscle exercises.

- myofascial release—pressing and stretching, sometimes with cooling and warming, of the muscles and soft tissues in the lower back, pelvic region, and upper legs. Also known as myofascial trigger point release.

- relaxation exercises

- biofeedback

- phytotherapy with plant extracts such as quercetin, bee pollen, and saw palmetto

- acupuncture

To help ensure coordinated and safe care, people should discuss their use of complementary and alternative medical practices, including their use of dietary supplements, with their health care provider. Read more at www.nccih.nih.gov.

For men whose chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome symptoms are affected by psychological stress, appropriate psychiatric treatment and stress reduction may reduce the recurrence of symptoms.

To help measure the effectiveness of treatment, a urologist may ask a series of questions from a standard questionnaire called the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index. The questionnaire helps a urologist assess the severity of symptoms and how they affect the man’s quality of life. A urologist may ask questions several times, such as before, during, and after treatment.

Acute bacterial prostatitis. A urologist treats acute bacterial prostatitis with antibiotics. The antibiotic prescribed may depend on the type of bacteria causing the infection. Urologists usually prescribe oral antibiotics for at least 2 weeks. The infection may come back; therefore, some urologists recommend taking oral antibiotics for 6 to 8 weeks. Severe cases of acute prostatitis may require a short hospital stay so men can receive fluids and antibiotics through an intravenous (IV) tube. After the IV treatment, the man will need to take oral antibiotics for 2 to 4 weeks. Most cases of acute bacterial prostatitis clear up completely with medication and slight changes to diet. The urologist may recommend

- avoiding or reducing intake of substances that irritate the bladder, such as alcohol, caffeinated beverages, and acidic and spicy foods

- increasing intake of liquids—64 to 128 ounces per day—to urinate often and help flush bacteria from the bladder

Chronic bacterial prostatitis. A urologist treats chronic bacterial prostatitis with antibiotics; however, treatment requires a longer course of therapy. The urologist may prescribe a low dose of antibiotics for up to 6 months to prevent recurrent infection. The urologist may also prescribe a different antibiotic or use a combination of antibiotics if the infection keeps coming back. The urologist may recommend increasing intake of liquids and avoiding or reducing intake of substances that irritate the bladder.

A urologist may use alpha blockers that treat chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome to treat urinary retention caused by chronic bacterial prostatitis. These medications help relax the bladder muscles near the prostate and lessen symptoms such as painful urination. Men may require surgery to treat urinary retention caused by chronic bacterial prostatitis. Surgically removing scar tissue in the urethra often improves urine flow and reduces urinary retention.

How can prostatitis be prevented?

Men cannot prevent prostatitis. Researchers are currently seeking to better understand what causes prostatitis and develop prevention strategies.

Eating, Diet, and Nutrition

Researchers have not found that eating, diet, and nutrition play a role in causing or preventing prostatitis. During treatment of bacterial prostatitis, urologists may recommend increasing intake of liquids and avoiding or reducing intake of substances that irritate the bladder. Men should talk with a health care provider or dietitian about what diet is right for them.

Clinical Trials

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and other components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct and support research into many diseases and conditions.

What are clinical trials, and are they right for you?

Clinical trials are part of clinical research and at the heart of all medical advances. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease. Researchers also use clinical trials to look at other aspects of care, such as improving the quality of life for people with chronic illnesses. Find out if clinical trials are right for you.

What clinical trials are open?

Clinical trials that are currently open and are recruiting can be viewed at ClinicalTrials.gov.

References

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Mark Litwin, M.D., University of California at Los Angeles; Anthony Schaeffer, M.D., Northwestern University; Michael P. O’Leary, M.D., M.P.H., Harvard Medical School