Link to Source page: /health-information/kidney-disease/children/ectopic-kidney

Current page state: This syndication page is Published

Ectopic Kidney

On this page:

- What is an ectopic kidney?

- What causes an ectopic kidney?

- How common is an ectopic kidney?

- What other health problems can an ectopic kidney cause?

- What are the symptoms of an ectopic kidney?

- How do health care professionals diagnose an ectopic kidney?

- How do health care professionals treat an ectopic kidney?

- Can I prevent an ectopic kidney?

- Clinical Trials for Ectopic Kidney

What is an ectopic kidney?

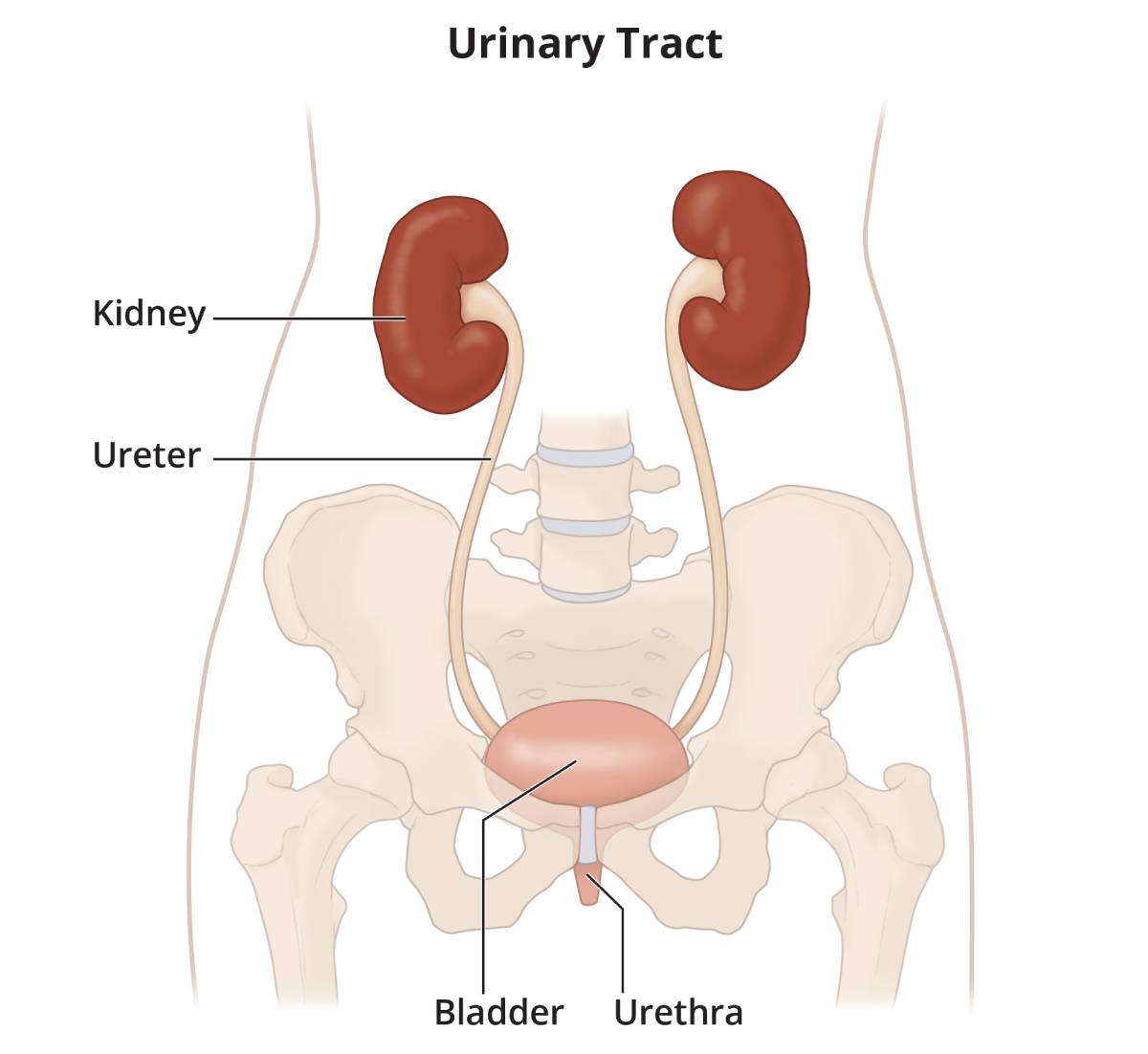

An ectopic kidney is a kidney located below, above, or on the opposite side of the kidney’s normal position in the urinary tract. The two kidneys are usually located near the middle of your back, just below your rib cage, on either side of your spine.

View full-sized image

View full-sized image An ectopic kidney usually doesn’t cause any symptoms or health problems, and many people never find out that they have the condition. If an ectopic kidney is discovered, it is usually found during a fetal ultrasound—an imaging test that uses sound waves to create a picture of how a baby is developing in the womb—or during medical tests done to check for a urinary tract infection or to find the cause of abdominal pain. Rarely does a person have two ectopic kidneys.

In the womb, a fetus’s kidneys first develop as small buds in the lower abdomen inside the pelvis. During the first 8 weeks of growth, the fetus’s kidneys slowly move from the pelvis to their normal position in the back near the rib cage. When an ectopic kidney occurs during growth, the kidney

- stays in the pelvis near the bladder

- stops moving up too early and stays in the lower abdomen

- moves too high up in the abdomen

- crosses over the center of the body and often grows into, or joins, the other kidney, with both kidneys on the same side of the body

Does ectopic kidney have another name?

When the kidney stays in the pelvis, it is called a pelvic kidney. If the kidney crosses to the other side of the body, it is called crossed renal ectopia.

View full-sized image

View full-sized image

What causes an ectopic kidney?

An ectopic kidney is a birth defect that happens while the fetus is developing. Researchers don’t know exactly what causes most birth defects, including ectopic kidney.

An ectopic kidney may result from

- a poorly developed kidney bud

- a problem in the kidney tissue that directs the developing kidney where to move

- a genetic defect that causes a genetic disorder

- an illness, infection, or drug or chemical reaction during fetal growth

How common is an ectopic kidney?

Most people who have an ectopic kidney don’t have symptoms, so researchers don’t know exactly how many people have one. Some studies suggest about 1 in 1,000 people has an ectopic kidney.1

What other health problems can an ectopic kidney cause?

An ectopic kidney usually doesn’t cause health problems, or complications, and may work normally. Most people are born with two kidneys, so if your ectopic kidney doesn’t work at all, your other kidney may be able to do the work both kidneys would have done. In rare cases, a nonfunctioning ectopic kidney must be removed. As long as the other kidney is working well, there should be no problems living with one kidney, also called a solitary kidney.

People who have an ectopic kidney are more likely to have vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). VUR is a condition in which urine flows backward from the bladder to one or both ureters, and sometimes to the kidneys. In some people, an ectopic kidney can block urine from correctly draining from the body or may be associated with VUR.

The abnormal placement of the ectopic kidney and potential problems with slow or blocked urine flow can be associated with other problems, including

- Urinary tract infection. In a urinary tract with slow or blocked urine drainage or VUR, bacteria in the urine is not flushed out of the urinary tract as it normally would be, which may lead to a urinary tract infection.

- Kidney stones. Kidney stones, also called urinary tract calculi, develop from minerals typically found in the urine, such as calcium and oxalate. When urine drainage is slower than normal, these minerals are more likely to build up and form kidney stones.

- Trauma. An ectopic kidney in your lower abdomen or pelvis or a fused ectopic kidney may be at greater risk for damage from certain kinds of injury or trauma. Talk with a health care professional if you or your child has an ectopic kidney and wants to play contact sports or participate in other activities that may result in injury to the kidney.

Talk with your health care professional about treatment options if you have any of these health problems.

In some cases, an ectopic kidney can block urine from correctly draining from your body.

In some cases, an ectopic kidney can block urine from correctly draining from your body.What are the symptoms of an ectopic kidney?

Most people with an ectopic kidney have no symptoms. If complications occur, however, symptoms may include

- pain in your abdomen or back

- urinary frequency or urgency, or burning during urination

- fever

- hematuria, or blood in the urine

- lump or mass in the abdomen

- high blood pressure

How do health care professionals diagnose an ectopic kidney?

Many people who have an ectopic kidney don’t discover it unless they have tests done for other reasons or the ectopic kidney was found during a prenatal ultrasound.

Health care professionals may use urinary tract imaging tests and lab tests to find out if you have an ectopic kidney and to rule out other health problems. If you have an ectopic kidney and it’s not causing symptoms or other health problems, you usually don’t need further testing or treatment.

Imaging tests

A specially trained technician performs imaging tests at an outpatient center or hospital, and a radiologist reviews the images.

Health care professionals use the following imaging tests to help diagnose and manage an ectopic kidney.

- Ultrasounds use sound waves to look at structures inside your body. The images can show the location of the kidneys.

- Voiding cystourethrograms use x-rays to show how urine flows through the bladder and urethra.

- Radionuclide scans, also called nuclear scans, may show the location and size of an ectopic kidney and may show any blockages in the urinary system.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses a magnetic field and radio waves—without radiation—to make pictures of your organs and structures inside your body. An MRI can show the location, size, shape, and function of the kidneys.

An ultrasound can show the location of your kidneys.

An ultrasound can show the location of your kidneys.Lab tests

A health care professional may do urine and blood tests to test your kidney function.

How do health care professionals treat an ectopic kidney?

Your health care professional may not need to treat your ectopic kidney if it isn’t causing symptoms or damage to your body or kidney. If tests show that you have a blockage or other potential complication in the urinary tract, your health care professional may suggest further follow-up or surgery to correct the abnormality.

If you have VUR with symptoms, a health care professional can evaluate and manage your VUR.

Can I prevent an ectopic kidney?

No. Like many other birth defects, health care professionals don’t know what causes or how to prevent an ectopic kidney.

Clinical Trials for Ectopic Kidney

The NIDDK conducts and supports clinical trials in many diseases and conditions, including kidney diseases. The trials look to find new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease and improve quality of life.

What are clinical trials, and are they right for you?

Clinical trials are part of clinical research and at the heart of all medical advances. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease. Researchers also use clinical trials to look at other aspects of care, such as improving the quality of life for people with chronic illnesses.

Find out if clinical trials are right for you.

Watch a video of NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers explaining the importance of participating in clinical trials.

What clinical trials are open?

Clinical trials that are currently open and are recruiting can be viewed at ClinicalTrials.gov.

References

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Linda M. Dairiki Shortliffe, M.D., Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford University