Link to Source page: /health-information/kidney-disease/children/hemolytic-uremic-syndrome

Current page state: This syndication page is Published

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome in Children

On this page:

- What is hemolytic uremic syndrome?

- What are the kidneys and what do they do?

- What causes hemolytic uremic syndrome in children?

- Which children are more likely to develop hemolytic uremic syndrome?

- What are the signs and symptoms of hemolytic uremic syndrome in children?

- Seek Immediate Care

- How is hemolytic uremic syndrome in children diagnosed?

- What are the complications of hemolytic uremic syndrome in children?

- How is hemolytic uremic syndrome in children treated?

- How can hemolytic uremic syndrome in children be prevented?

- Eating, Diet, and Nutrition

- Clinical Trials

What is hemolytic uremic syndrome?

Hemolytic uremic syndrome, or HUS, is a kidney condition that happens when red blood cells are destroyed and block the kidneys' filtering system. Red blood cells contain hemoglobin—an iron-rich protein that gives blood its red color and carries oxygen from the lungs to all parts of the body.

When the kidneys and glomeruli—the tiny units within the kidneys where blood is filtered—become clogged with the damaged red blood cells, they are unable to do their jobs. If the kidneys stop functioning, a child can develop acute kidney injury—the sudden and temporary loss of kidney function. Hemolytic uremic syndrome is the most common cause of acute kidney injury in children.

What are the kidneys and what do they do?

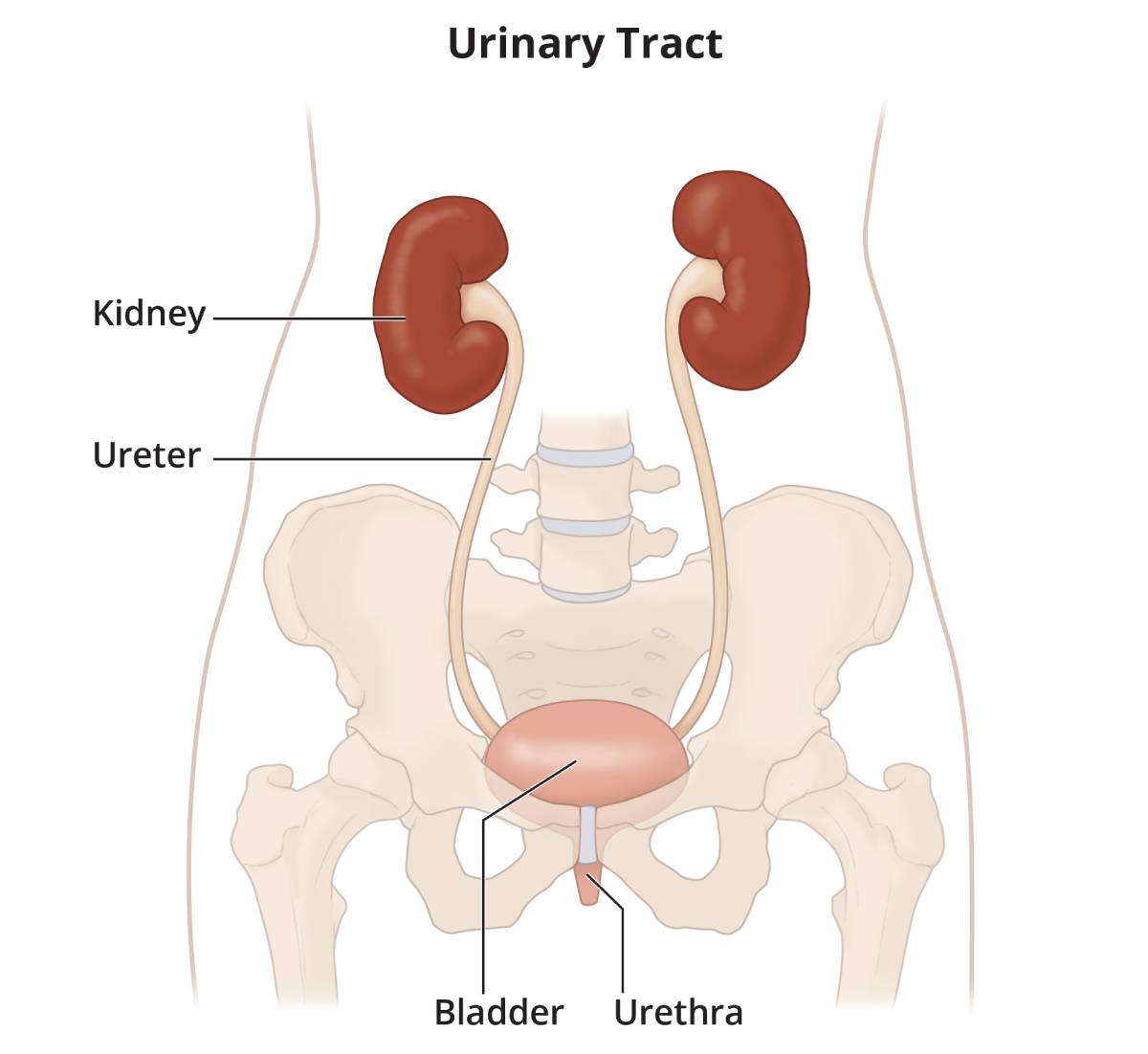

The kidneys are two bean-shaped organs, each about the size of a fist. They are located just below the rib cage, one on each side of the spine. Every day, the two kidneys filter about 120 to 150 quarts of blood to produce about 1 to 2 quarts of urine, composed of wastes and extra fluid. Children produce less urine than adults and the amount produced depends on their age. The urine flows from the kidneys to the bladder through tubes called ureters. The bladder stores urine. When the bladder empties, urine flows out of the body through a tube called the urethra, located at the bottom of the bladder.

What causes hemolytic uremic syndrome in children?

The most common cause of hemolytic uremic syndrome in children is an Escherichia coli (E. coli) infection of the digestive system. The digestive system is made up of the gastrointestinal, or GI, tract—a series of hollow organs joined in a long, twisting tube from the mouth to the anus—and other organs that help the body break down and absorb food.

Normally, harmless strains, or types, of E. coli are found in the intestines and are an important part of digestion. However, if a child becomes infected with the O157:H7 strain of E. coli, the bacteria will lodge in the digestive tract and produce toxins that can enter the bloodstream. The toxins travel through the bloodstream and can destroy the red blood cells. E.coli O157:H7 can be found in

- undercooked meat, most often ground beef

- unpasteurized, or raw, milk

- unwashed, contaminated raw fruits and vegetables

- contaminated juice

- contaminated swimming pools or lakes

Less common causes, sometimes called atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, can include

- taking certain medications, such as chemotherapy

- having other viral or bacterial infections

- inheriting a certain type of hemolytic uremic syndrome that runs in families

Which children are more likely to develop hemolytic uremic syndrome?

Children who are more likely to develop hemolytic uremic syndrome include those who

- are younger than age 5 and have been diagnosed with an E. coli O157:H7 infection

- have a weakened immune system

- have a family history of inherited hemolytic uremic syndrome

Hemolytic uremic syndrome occurs in about two out of every 100,000 children.

What are the signs and symptoms of hemolytic uremic syndrome in children?

A child with hemolytic uremic syndrome may develop signs and symptoms similar to those seen with gastroenteritis—an inflammation of the lining of the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine— such as

- vomiting

- bloody diarrhea

- abdominal pain

- fever and chills

- headache

As the infection progresses, the toxins released in the intestine begin to destroy red blood cells. When the red blood cells are destroyed, the child may experience the signs and symptoms of anemia—a condition in which red blood cells are fewer or smaller than normal, which prevents the body's cells from getting enough oxygen.

Signs and symptoms of anemia may include

- fatigue, or feeling tired

- weakness

- fainting

- paleness

As the damaged red blood cells clog the glomeruli, the kidneys may become damaged and make less urine. When damaged, the kidneys work harder to remove wastes and extra fluid from the blood, sometimes leading to acute kidney injury.

Other signs and symptoms of hemolytic uremic syndrome may include bruising and seizures.

When hemolytic uremic syndrome causes acute kidney injury, a child may have the following signs and symptoms:

- edema—swelling, most often in the legs, feet, or ankles and less often in the hands or face

- albuminuria—when a child's urine has high levels of albumin, the main protein in the blood

- decreased urine output

- hypoalbuminemia—when a child's blood has low levels of albumin

- blood in the urine

How is hemolytic uremic syndrome in children diagnosed?

A health care provider diagnoses hemolytic uremic syndrome with

- a medical and family history

- a physical exam

- urine tests

- a blood test

- a stool test

- kidney biopsy

Medical and Family History

Taking a medical and family history is one of the first things a health care provider may do to help diagnose hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Physical Exam

A physical exam may help diagnose hemolytic uremic syndrome. During a physical exam, a health care provider most often

- examines a child's body

- taps on specific areas of the child's body

Urine Tests

A health care provider may order the following urine tests to help determine if a child has kidney damage from hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Dipstick test for albumin. A dipstick test performed on a urine sample can detect the presence of albumin in the urine, which could mean kidney damage. The child or caretaker collects a urine sample in a special container in a health care provider's office or a commercial facility. For the test, a nurse or technician places a strip of chemically treated paper, called a dipstick, into the child's urine sample. Patches on the dipstick change color when albumin is present in the urine.

Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio. A health care provider uses this measurement to estimate the amount of albumin passed into the urine over a 24-hour period. The child provides a urine sample during an appointment with the health care provider. Creatinine is a waste product that is filtered in the kidneys and passed in the urine. A high urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio indicates that the kidneys are leaking large amounts of albumin into the urine.

Blood Test

A blood test involves drawing blood at a health care provider's office or a commercial facility and sending the sample to a lab for analysis. A health care provider will test the blood sample to

- estimate how much blood the kidneys filter each minute, called the estimated glomerular filtration rate, or eGFR. The test results help the health care provider determine the amount of kidney damage from hemolytic uremic syndrome.

- check red blood cell and platelet levels.

- check for liver and kidney function.

- assess protein levels in the blood.

Stool Test

A stool test is the analysis of a sample of stool. The health care provider will give the child's parent or caretaker a container for catching and storing the stool. The parent or caretaker returns the sample to the health care provider or a commercial facility that will send the sample to a lab for analysis. Stool tests can show the presence of E. coli O157:H7.

Kidney Biopsy

Biopsy is a procedure that involves taking a small piece of kidney tissue for examination with a microscope. A health care provider performs the biopsy in an outpatient center or a hospital. The health care provider will give the child light sedation and local anesthetic; however, in some cases, the child will require general anesthesia. A pathologist—a doctor who specializes in diagnosing diseases—examines the tissue in a lab. The pathologist looks for signs of kidney disease and infection. The test can help diagnose hemolytic uremic syndrome.

What are the complications of hemolytic uremic syndrome in children?

Most children who develop hemolytic uremic syndrome and its complications recover without permanent damage to their health.1

However, children with hemolytic uremic syndrome may have serious and sometimes life-threatening complications, including

- acute kidney injury

- high blood pressure

- blood-clotting problems that can lead to bleeding

- seizures

- heart problems

- chronic, or long lasting, kidney disease

- stroke

- coma

How is hemolytic uremic syndrome in children treated?

A health care provider will treat a child with hemolytic uremic syndrome by addressing

- urgent symptoms and preventing complications

- acute kidney injury

- chronic kidney disease (CKD)

In most cases, health care providers do not treat children with hemolytic uremic syndrome with antibiotics unless they have infections in other areas of the body. With proper management, most children recover without long-term health problems.2

Treating Urgent Symptoms and Preventing Complications

A health care provider will treat a child's urgent symptoms and try to prevent complications by

- observing the child closely in the hospital

- replacing minerals, such as potassium and salt, and fluids through an intravenous (IV) tube

- giving the child red blood cells and platelets— cells in the blood that help with clotting—through an IV

- giving the child IV nutrition

- treating high blood pressure with medications

Treating Acute Kidney Injury

If necessary, a health care provider will treat acute kidney injury with dialysis—the process of filtering wastes and extra fluid from the body with an artificial kidney. The two forms of dialysis are hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Most children with acute kidney injury need dialysis for a short time only.

Treating Chronic Kidney Disease

Some children may sustain significant kidney damage that slowly develops into CKD. Children who develop CKD must receive treatment to replace the work the kidneys do. The two types of treatment are dialysis and transplantation.

In most cases, health care providers treat CKD with a kidney transplant. A kidney transplant is surgery to place a healthy kidney from someone who has just died or a living donor, most often a family member, into a person's body to take over the job of the failing kidney. Though some children receive a kidney transplant before their kidneys fail completely, many children begin with dialysis to stay healthy until they can have a transplant.

How can hemolytic uremic syndrome in children be prevented?

Parents and caregivers can help prevent childhood hemolytic uremic syndrome due to E. coli O157:H7 by

- avoiding unclean swimming areas

- avoiding unpasteurized milk, juice, and cider

- cleaning utensils and food surfaces often

- cooking meat to an internal temperature of at least 160° F

- defrosting meat in the microwave or refrigerator

- keeping children out of pools if they have had diarrhea

- keeping raw foods separate

- washing hands before eating

- washing hands well after using the restroom and after changing diapers

When a child is taking medications that may cause hemolytic uremic syndrome, it is important that the parent or caretaker watch for symptoms and report any changes in the child's condition to the health care provider as soon as possible.

Eating, Diet, and Nutrition

At the beginning of the illness, children with hemolytic uremic syndrome may need IV nutrition or supplements to help maintain fluid balance in the body. Some children may need to follow a low-salt diet to help prevent swelling and high blood pressure.

Health care providers will encourage children with hemolytic uremic syndrome to eat when they are hungry. Most children who completely recover and do not have permanent kidney damage can return to their usual diet.

Resources

National Kidney Foundation

Children with Chronic Kidney Disease: Tips for Parents

Nemours KidsHealth Website

When Your Child Has a Chronic Kidney Disease

What's the Deal With Dialysis?

United Network for Organ Sharing

Organ Transplants: What Every Kid Needs to Know (PDF, 1.67 MB)

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Medicare Coverage of Kidney Dialysis & Kidney Transplant Services

U.S. Social Security Administration

Benefits For Children With Disabilities (PDF, 413 KB)

Clinical Trials

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and other components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct and support research into many diseases and conditions.

What are clinical trials and what role do children play in research?

Clinical trials are research studies involving people of all ages. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease. Researchers also use clinical trials to look at other aspects of care, such as improving quality of life. Research involving children helps scientists

- identify care that is best for a child

- find the best dose of medicines

- find treatments for conditions that only affect children

- treat conditions that behave differently in children

- understand how treatment affects a growing child’s body

Find out more about clinical trials and children.

What clinical trials are open?

Clinical trials that are currently open and are recruiting can be viewed at ClinicalTrials.gov.

References

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Barbara Fivush, M.D., and Kathy Jabs, M.D., of the American Society of Pediatric Nephrology (ASPN); Tej Mattoo, M.D.; William Primack, M.D.; Joseph Flynn, M.D.; Ira Davis, M.D.; Ann Guillott, M.D.; Steve Alexander, M.D.; Deborah Kees-Folts, M.D.; Alicia Neu, M.D.; Steve Wassner, M.D.; John Brandt, M.D.; and Manju Chandra, M.D., all members of the ASPN's Clinical Affairs Committee. Frederick Kaskel, M.D., Ph.D., ASPN; Sharon Andreoli, M.D., ASPN