Link to Source page: /health-information/kidney-disease/children/multicystic-dysplastic-kidney

Current page state: This syndication page is Published

Multicystic Dysplastic Kidney

On this page:

- What is multicystic dysplastic kidney?

- Does MCDK have other names?

- How common is MCDK?

- Who is more likely to develop MCDK?

- What are the complications of MCDK?

- What are the symptoms of MCDK?

- What causes MCDK?

- How do health care professionals diagnose MCDK?

- How do health care professionals treat MCDK?

- Can MCDK be prevented?

- How do eating, diet, and nutrition affect MCDK?

- Clinical Trials for Multicystic Dysplastic Kidney

What is multicystic dysplastic kidney?

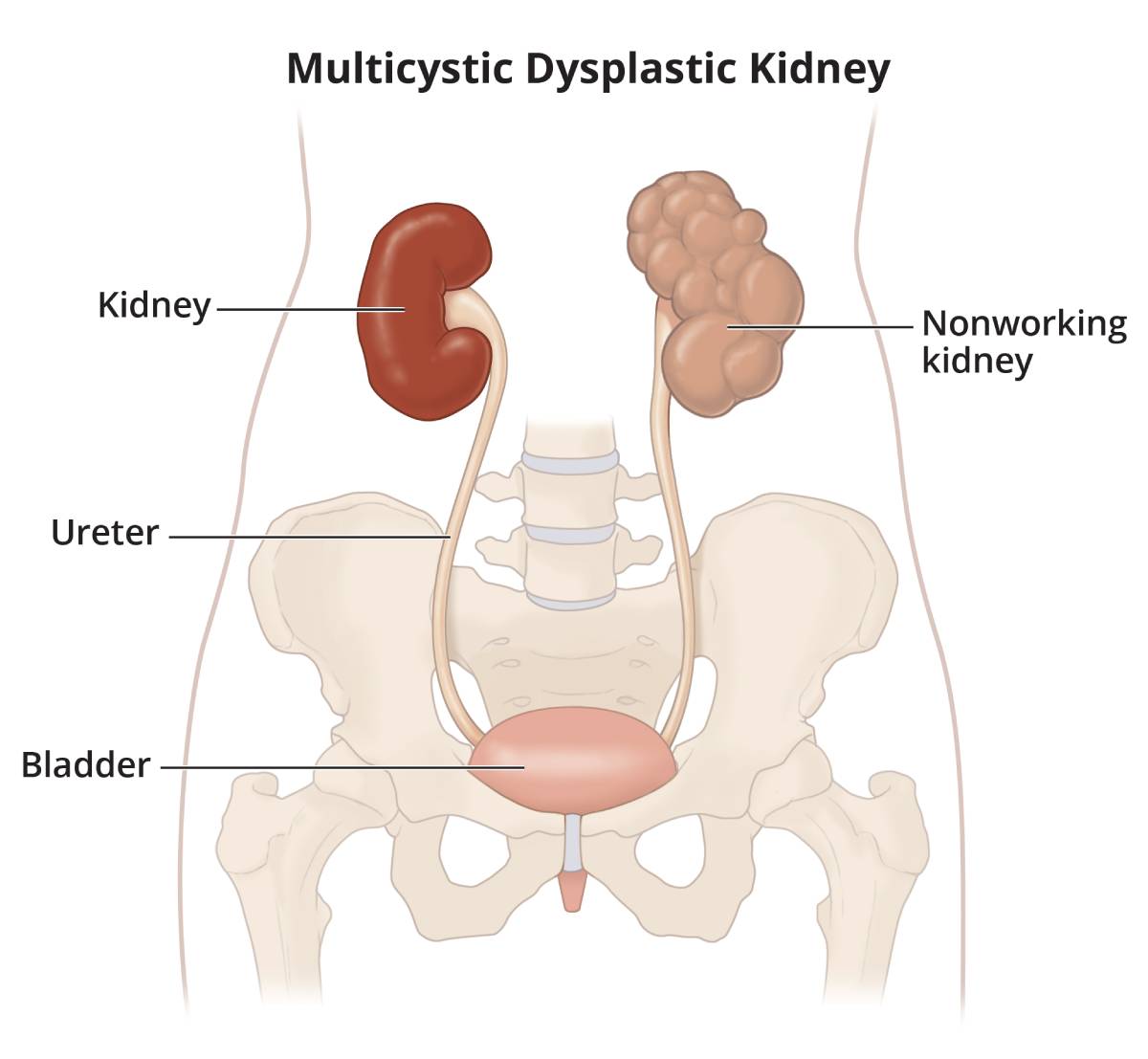

Multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK) is a condition in which one or both of a baby’s kidneys do not develop normally while the baby is growing in the womb. Fluid-filled sacs, called cysts, replace normal kidney tissue and prevent the affected kidney from working.

When only one kidney is affected, the unaffected kidney usually grows larger to compensate for the nonworking kidney, and it does the work of both kidneys. The nonworking kidney usually shrinks and disappears over time. The remaining, working kidney is called a solitary or single-functioning kidney. A health care professional may need to evaluate the unaffected kidney to make sure it is working properly.

Babies born with MCDK in only one kidney can grow normally and may have few, if any, health problems. Babies born with MCDK in both kidneys may not survive long after birth. Babies who do survive often develop kidney failure and require kidney replacement therapy—dialysis or a kidney transplant.

MCDK is different from polycystic kidney disease, which is a disorder that causes fluid-filled cysts to grow in the kidneys.

MCDK most often occurs in one kidney, and the unaffected kidney does the work of both kidneys.

MCDK most often occurs in one kidney, and the unaffected kidney does the work of both kidneys.

Does MCDK have other names?

MCDK may also be called multicystic renal dysplasia.

How common is MCDK?

A small study estimated that between 1 in 1,000 babies and 1 in 4,300 babies are born with MCDK each year.1 However, some babies with MCDK are never diagnosed with the condition, so researchers don’t know exactly how many people have MCDK.

Who is more likely to develop MCDK?

MCDK is more likely to occur in babies or fetuses who have

- parents with genetic traits for the condition

- certain genetic syndromes that affect multiple parts of the body

MCDK is more common in boys than in girls.1

What are the complications of MCDK?

Some children with MCDK may develop high blood pressure, also called hypertension.

Children with MCDK in one kidney may have other urinary tract problems that affect their working kidney. These problems may increase the child’s risk of developing chronic kidney disease.

What are the symptoms of MCDK?

Many babies born with MCDK in only one kidney have no signs of the condition. In some babies, the affected kidney may be bigger than normal at birth and may cause pain.

What causes MCDK?

MCDK is a birth defect that happens when the fetus is developing in the womb. Researchers don’t know exactly what causes MCDK, but it may be caused by

- gene mutations that can pass from parent to child, although a genetic cause is usually not found

- genetic syndromes that affect more than one system in the body, such as the digestive system, nervous system, heart and blood vessels, muscles and bones, or other parts of the urinary tract

How do health care professionals diagnose MCDK?

Most often, MCDK is diagnosed before birth, during a prenatal ultrasound. Ultrasounds use sound waves to create a picture of how a baby is developing in the womb. The images can show problems with the fetus’s kidneys and other parts of the urinary tract. Ultrasounds during pregnancy are part of regular prenatal testing. After the baby is born, a health care professional will perform an ultrasound on the baby to confirm the diagnosis.

MCDK is most often diagnosed before birth during a prenatal ultrasound.

MCDK is most often diagnosed before birth during a prenatal ultrasound.

In some cases, MCDK is diagnosed after a baby is born. Health care professionals may diagnose MCDK when performing an ultrasound on the baby to check for another medical problem, such as a problem with the urinary tract that may be causing urinary tract infections.

How do health care professionals treat MCDK?

Health care professionals may not need to treat MCDK if the baby has no signs of the condition and only one kidney is affected and the other kidney is healthy. However, health care professionals will suggest regular checkups that include

- blood pressure tests

- blood tests to check how well the kidneys are working

- urine tests to look for protein in the urine and check for kidney damage

- regular ultrasounds to monitor for disappearance of the affected kidney and to make sure the other kidney continues to grow and stay healthy

In rare cases, if the affected kidney doesn’t shrink over time, your child’s health care professional may recommend surgery to remove the nonworking kidney if it is causing problems, such as high blood pressure or kidney infections.

If both kidneys are affected or the healthy kidney becomes damaged, your child may need kidney replacement therapy—kidney transplant, hemodialysis, or peritoneal dialysis—to stay healthy.

If your child’s health care professional suspects your child has kidney disease, you may be referred to a pediatric nephrologist—a doctor who specializes in treating kidney disease in children.

Can MCDK be prevented?

Researchers have not yet found a way to prevent MCDK.

How do eating, diet, and nutrition affect MCDK?

Researchers have not found that eating, diet, and nutrition play a role in causing or preventing MCDK.

If your child’s kidney function is reduced, your child’s health care professional may suggest changes to what your child eats and drinks to slow the progress of the kidney disease in the unaffected kidney. Talk with your child’s health care professional before making any changes to your child’s diet. Your child’s health care professional may suggest you work with a registered dietitian to create an eating plan with the right foods and nutrients in the right amounts for your child to stay healthy.

Clinical Trials for Multicystic Dysplastic Kidney

The NIDDK conducts and supports clinical trials in many diseases and conditions, including kidney diseases. The trials look to find new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease and improve quality of life.

Why are clinical trials with children important?

Children respond to medicines and treatments differently than adults. The way to get the best treatments for children is through research designed specifically for them.

We have already made great strides in improving children’s health outcomes through clinical trials—and other types of clinical studies. Vaccines, treatments for children with cancer, and interventions for premature babies are just a few examples of how this targeted research can help. However, we still have many questions to answer and more children waiting to benefit.

The data gathered from trials and studies involving children help health care professionals and researchers

- find the best dose of medicines for children

- find treatments for conditions that only affect children

- treat conditions that behave differently in children than in adults

- understand the differences in children as they grow

How do I decide if a clinical trial is right for my child?

We understand you have many questions, want to weigh the pros and cons, and need to learn as much as possible. Deciding to enroll in a study can be life changing for you and for your child. Depending on the outcome of the study, your child may find relief from their condition, see no benefit, or help to improve the health of future generations.

Talk with your child and consider what would be expected. What could be the potential benefit or harm? Would you need to travel? Is my child well enough to participate? While parents or guardians must give their permission, or consent, for their children to join a study, the children must also agree to participate, if they are capable (verbal). In the end, no choice is right or wrong. Your decision is about what is best for your child.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is committed to ensuring you get all the information you need to feel comfortable and make informed decisions. The safety of children remains the utmost priority for all NIH research studies. For more resources to help decide if clinical trials are right for your child, visit Clinical Trials and You: For Parents and Children.

What aspects of MCDK are being studied in children?

Researchers study many aspects of multicystic dysplastic kidney in children, such as therapies to improve survival rates of fetuses with kidney problems.

Watch a video of NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers explaining the importance of participating in clinical trials.

What clinical studies for MCDK are available for child participants?

You can view a filtered list of clinical studies on MCDK that are federally funded, open, and recruiting at www.ClinicalTrials.gov. You can expand or narrow the list to include clinical studies from industry, universities, and individuals; however, the NIH does not review these studies and cannot ensure they are safe. If you find a trial you think may be right for your child, talk with your child’s health care provider about how to enroll.

Reference

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

NIDDK would like to thank:

Deepa H. Chand, M.D., M.H.S.A., FASN; University of Illinois College of Medicine-Peoria, Children’s Hospital of Illinois