Link to Source page: /health-information/urologic-diseases/urinary-diversion

Current page state: This syndication page is Published

Urinary Diversion

On this page:

- What is urinary diversion?

- Why might I need a urinary diversion?

- What are the types of urinary diversions?

- What should I expect after urinary diversion surgery?

- Will my diet need to change after urinary diversion?

- Clinical Trials for Urinary Diversion

What is urinary diversion?

Urinary diversion is a surgical procedure that creates a new way for urine to exit your body when urine flow is blocked or when there is a need to bypass a diseased area in the urinary tract.

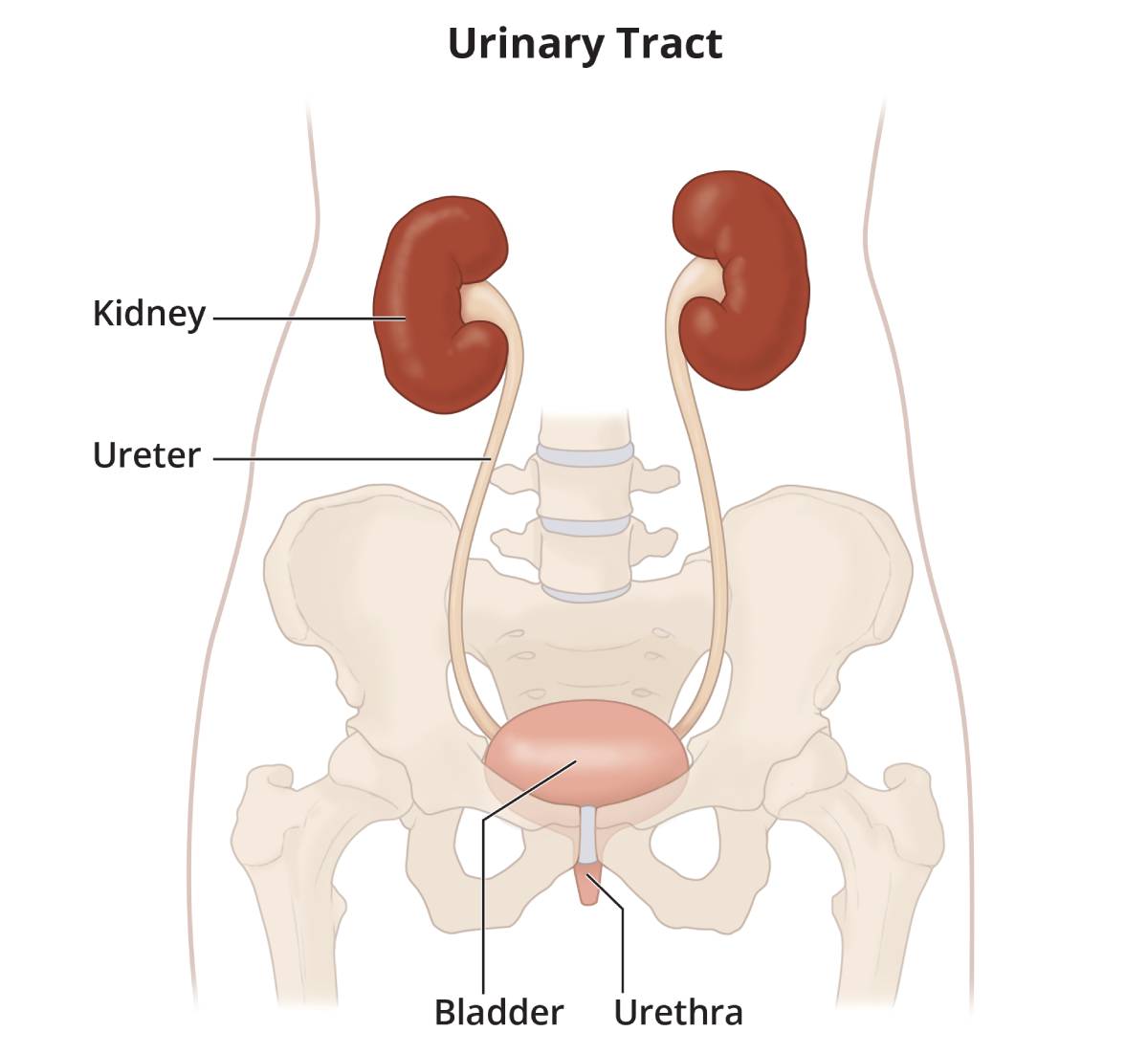

The urinary tract is your body’s drainage system for removing urine, which is made of wastes and extra fluid. Your urinary tract is designed to have the urine flow from the kidneys, through the ureters, to the bladder, and out the urethra. When the urine can’t flow normally, it may build up in your bladder, ureters, or kidneys. This buildup of urine may cause pain, urinary tract infections, urinary stones or calculi, damage to your urinary tract, or kidney failure. If left untreated, a buildup of urine in the urinary tract can be life-threatening.

View full-sized image All parts of the urinary tract—the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra—must work together to urinate normally.

All parts of the urinary tract—the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra—must work together to urinate normally.

Urinary diversion may be temporary—the flow of urine is rerouted for several days, weeks, or sometimes months until the urine can flow normally again—or permanent—surgery is done to create a permanent change to the way urine flows through the body.

Why might I need a urinary diversion?

The most common reason you might need a urinary diversion is bladder cancer that requires the bladder to be removed—a procedure called a cystectomy.

Other reasons for a urinary diversion include

- nerve damage to the bladder caused by birth defects such as spina bifida, spinal cord injury, or multiple sclerosis

- chronic—or long lasting—inflammation of the bladder, which may result from severe cases of interstitial cystitis, recurrent urinary tract infections, or chronic urinary retention

- conditions that cause outside pressure to the urethra or one or both ureters

- chronic urinary retention from an enlarged prostate or benign prostatic hyperplasia

- radiation therapy that results in permanent damage to the bladder

- severe urinary incontinence that can’t be managed with standard treatments

- trauma to the bladder, urethra, or pelvis

- tumors in the genitourinary tract or adjacent tissues and organs

- urinary stones

What are the types of urinary diversions?

The main types of urinary diversion include

Bladder catheterization

Bladder catheterization involves inserting a thin, flexible tube—called a catheter—into the bladder to drain urine. The urine drains into a collection bag outside the body. The two types of urinary catheters include

- Foley catheter, inserted into the bladder through the urethra

- suprapubic catheter, inserted into the bladder through a small hole in the skin beneath the belly button

Urinary catheters may remain in place for several days or weeks while tissues heal after urinary tract surgery or treatment of urinary blockage and, in some cases, may be permanent. Catheters that are in place for longer periods of time need to be replaced with a new catheter periodically.

Cystostomy

A cystostomy is a surgical procedure where a doctor inserts a small tube into your bladder through the skin of the lower abdomen. The tube allows urine to drain from your bladder into a bag outside your body.

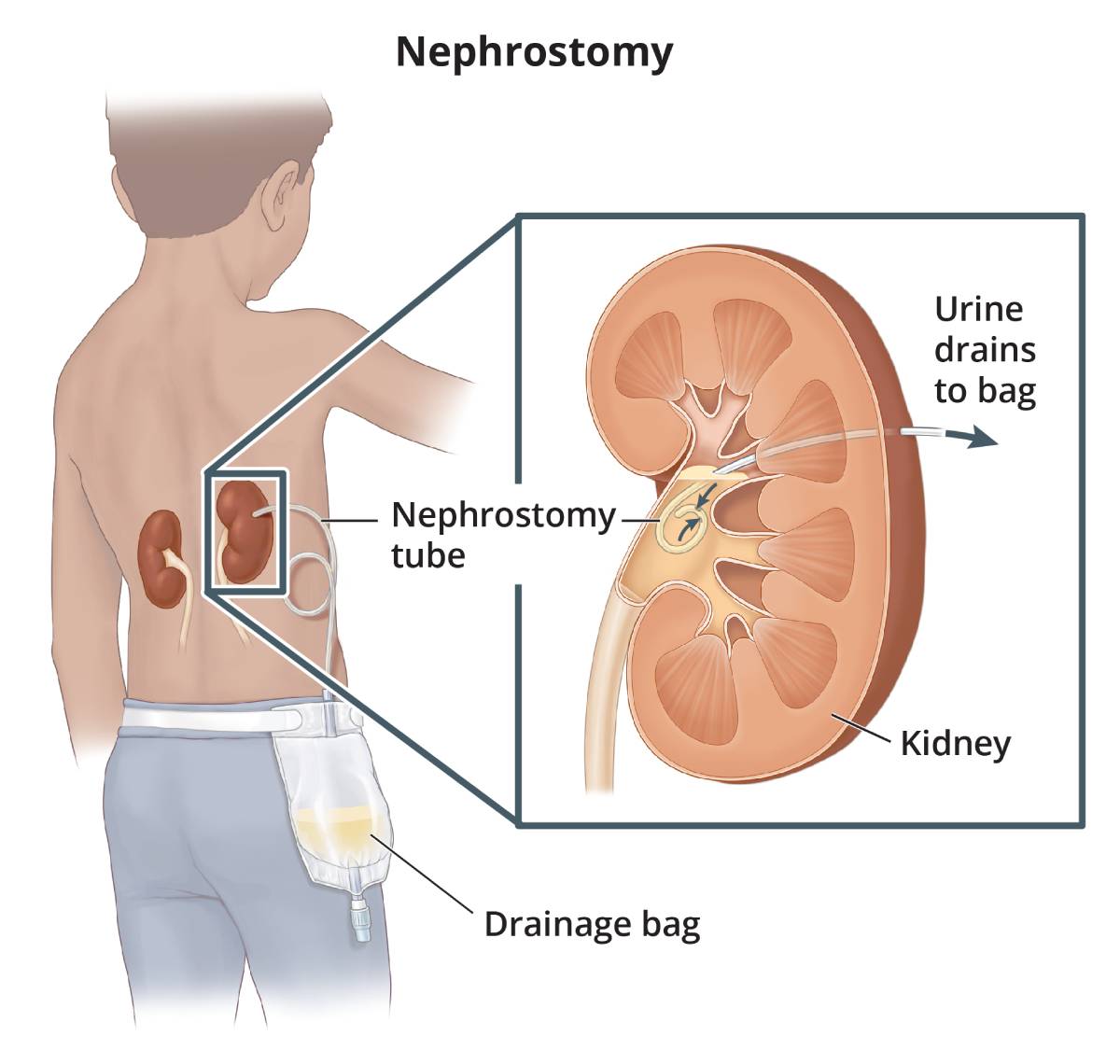

Nephrostomy

Similar to a cystostomy, during a nephrostomy a surgeon or radiologist makes a tiny incision and inserts a small tube, called a nephrostomy tube, through the skin of your back into your kidney. The nephrostomy tube allows urine to drain from your kidney into a bag outside your body.

You may need a nephrostomy when being treated for a kidney stone or when your ureters are narrowed, blocked, or inflamed. Depending on the reason for the nephrostomy and how quickly your body heals, the nephrostomy tube may be used for different lengths of time.

View full-sized image Nephrostomy tube and external drainage pouch.

Nephrostomy tube and external drainage pouch.

Ureteral stent

A ureteral stent is a thin flexible tube that is inserted into the ureter to help urine flow from the kidney to the bladder. The ureteral stent is guided with a cystoscope into your ureter, then one end of the stent is placed in the kidney and the other end is placed in the bladder.

You may need a ureteral stent if one of your ureters is blocked as a result of surgery, a kidney stone, a tumor, or infection. A ureteral stent is usually temporary but, in some cases, can be used to permanently manage a blockage of the ureter. Ureteral stents that are in place for longer periods of time need to be replaced periodically.

Urostomy

A urostomy is a stoma, or opening, in your abdomen that connects to your urinary tract to allow urine to drain freely from your body. Urine is collected and stored in a small bag, called a urostomy pouch, which you can empty at your convenience. The pouch is attached to the skin around your stoma and worn outside your body.

The two main types of urostomy include

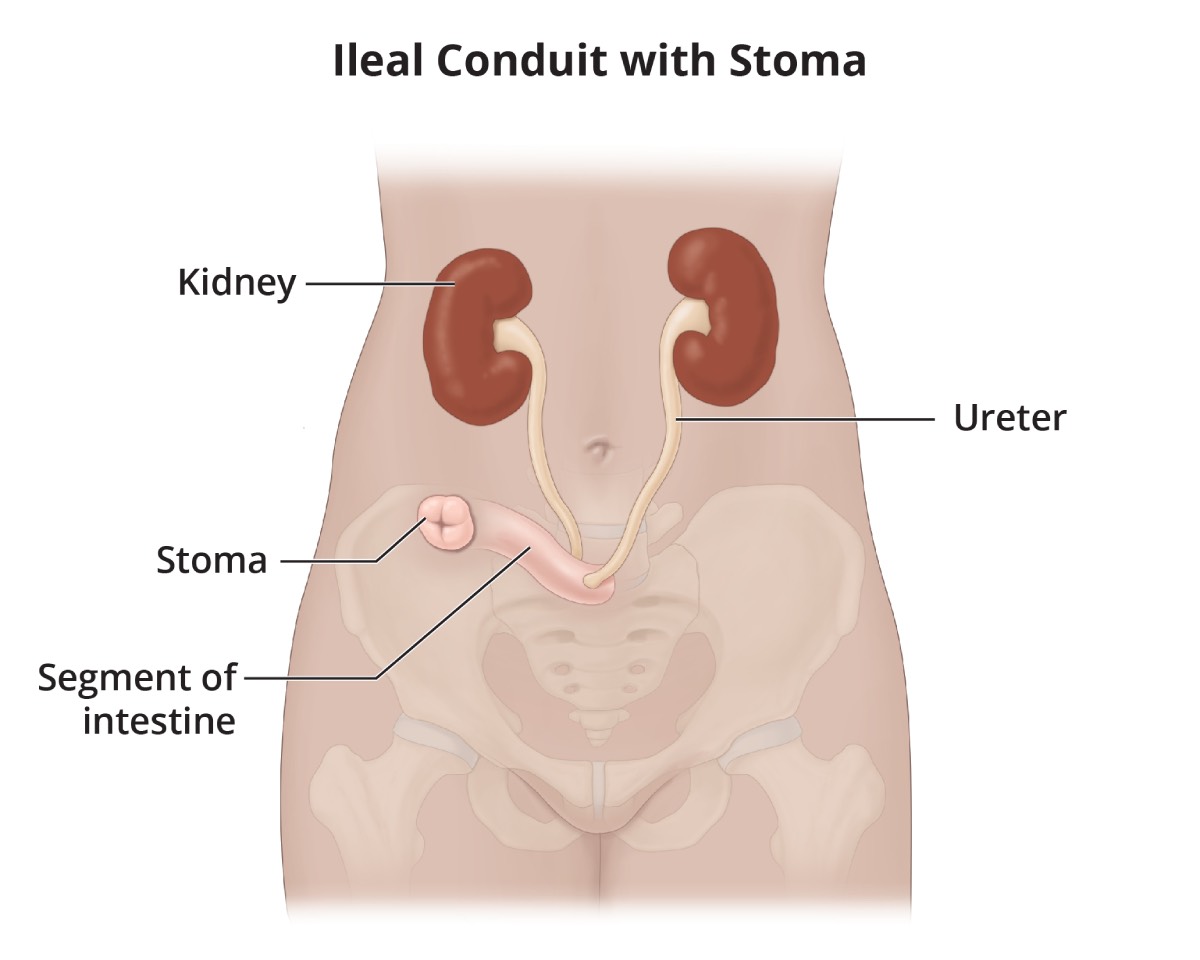

- Ileal conduit. A surgeon removes a piece of your intestine to create a passageway for urine. The ureters are attached to the piece of intestine, then the intestine is attached to an opening in your abdomen, creating a stoma. The urine flows from the ureters, through the piece of intestine, and out the stoma.

- Cutaneous ureterostomy. A surgeon attaches one or both ureters directly to a stoma in your abdomen.

An ileal conduit is created by attaching both ureters to a piece of intestine, then connecting the intestine to a stoma.

View full-sized image

An ileal conduit is created by attaching both ureters to a piece of intestine, then connecting the intestine to a stoma.

View full-sized image A cutaneous ureterostomy is created by attaching one or both ureters to a stoma.

A cutaneous ureterostomy is created by attaching one or both ureters to a stoma.

Continent urinary diversion

Continent urinary diversion collects and stores urine inside the body until you drain the urine using a catheter or you urinate through the urethra. The urine flows through the ureters and is stored in an internal pouch created from part of your bowel or in your bladder. Continent urinary diversion allows you to control when urine leaves your body.

The main types of continent urinary diversion include

- Continent cutaneous reservoir. A surgeon uses a piece of your bowel to create an internal pouch, or reservoir, to hold urine. The internal pouch is placed inside your abdomen. The ureters are attached to the internal pouch, and the internal pouch is attached to a stoma in your abdomen. Urine flows through the ureters and into the internal pouch, where it is stored until you drain the urine by inserting a catheter into the stoma. The stoma is the end of a channel that connects to the reservoir. The channel has a valve that prevents urine from exiting the body until a catheter is inserted. The channel can be created from a piece of intestine or by using the appendix.

- Bladder substitute, or neobladder. A surgeon uses a piece of your bowel to create an internal reservoir, called a bladder substitute or neobladder, to hold urine. The bladder substitute is placed in the pelvis. The ureters are attached to the bladder substitute, and the bladder substitute is attached to the urethra. Urine flows through the ureters, into the bladder substitute, and you urinate through the urethra.

A continent cutaneous reservoir is created using an internal pouch to hold urine. Both ureters are attached to the pouch and a channel connects the pouch to a stoma.

View full-sized image

A continent cutaneous reservoir is created using an internal pouch to hold urine. Both ureters are attached to the pouch and a channel connects the pouch to a stoma.

View full-sized image A bladder substitute is created using a piece of bowel to hold urine.

A bladder substitute is created using a piece of bowel to hold urine.

The type of urinary diversion procedure you have depends on different factors, including your age, prior medical history, previous surgeries, how well you can move around, if you’ve had radiation therapy or cancer, your ability to use a catheter, and your preference.

What should I expect after urinary diversion surgery?

A nurse will teach you how to manage and care for your urinary diversion. Talk with your health care professional about any questions or concerns you have caring for or living with your stoma, urostomy pouch, continent cutaneous reservoir, or bladder substitute.

Always wash your hands with soap and water before and after caring for your urinary diversion to avoid introducing bacteria or other foreign substances that could lead to infection.

Caring for a stoma

Care for your stoma every day to keep the stoma and skin around the stoma clean and healthy.

- Gently wipe away mucus.

- Wash the stoma and surrounding skin with warm water.

- If using soap, choose mild soap only.

- Rinse the stoma and surrounding skin thoroughly.

- Avoid products that contain oils, fragrance, deodorants, alcohol, or harsh chemicals.

- Gently pat the stoma and surrounding skin dry completely.

- Inspect the stoma and surrounding skin and contact your health care professional if you notice any skin changes or irritation.

Living with a urostomy pouch, continent cutaneous reservoir, or bladder substitute

Urostomy pouch. If you have an ileal conduit or cutaneous ureterostomy, you need to care for your urostomy pouch, also called a pouching system. You either have a two-piece pouching system with a barrier that sticks to the skin and a pouch that attaches to the barrier, or a one-piece system with a skin barrier and pouch combined as a single unit. The skin barrier, also called a wafer, fits over your stoma and is designed to protect your skin. You empty the urine by opening a valve on the pouch and drain the urine into a toilet.

Your pouching system is designed to prevent urine leaks, protect your skin from urine, keep the skin around your stoma healthy, and avoid odor. Steps to care for your pouch include

- emptying the pouch often—empty the pouch when it is one-third to one-half full to avoid leaks, skin irritation, and odor

- changing the pouch regularly—most pouches need to be changed 1 to 2 times per week, but how often you need to change your pouch depends on the type of pouch you wear, how well the skin barrier fits, the condition of the skin around your stoma, your activity level, your body shape, and your level of perspiration

- keeping the skin around the stoma clean—each time you change the pouch, gently clean the skin around the stoma and dry the skin completely before putting on a new pouch

At night, you can attach a piece of flexible tubing to the drain valve on your pouch to allow urine to flow into a night drainage unit while you sleep.

Talk with your health care professionals about the best way to care for your pouching system. They may suggest ostomy products such as ostomy powder or skin sealant to avoid skin irritation or to help the pouching system stick to your skin better.

You do not need special clothing with a urostomy pouch. Pouches are available in many different types to fit your body, so they aren’t noticeable under clothing. You may want to tuck your pouch inside your underwear or undergarments, wear snug underwear, or wear a belt that attaches to the pouch for extra support and security.

Continent cutaneous reservoir. Talk with your health care professional about how to care for your continent cutaneous reservoir, including how often to drain and irrigate the internal pouch or bladder. In general, you will

- empty the internal pouch or bladder by inserting a catheter through the stoma to drain the urine—every 2 hours for the first few weeks after urinary diversion surgery, and every 4 to 6 hours as the pouch stretches and can hold more urine or as your bladder heals

- keep the skin around the stoma clean—before and after you use a catheter, gently clean the skin around the stoma and dry the skin completely

- irrigate, or flush out, the internal pouch using a syringe and sterile water or normal saline to remove mucus that can build up inside the pouch

If you have trouble inserting the catheter into your stoma, contact your health care professional right away.

Bladder substitute, or neobladder. Talk with your health care professional about how to care for your bladder substitute. It is important that you take steps to make sure the bladder substitute does not get overstretched, including

- empty your bladder substitute often—every 2 to 3 hours during the day and every 3 to 4 hours at night for the first few weeks after urinary diversion surgery, gradually lengthening to every 4 to 6 hours during the day and at least once at night

- sit on the toilet, even if you are a man, and bear down slightly using your abdominal muscles to fully empty your bladder substitute

- use a catheter to empty your bladder substitute if it isn’t emptying completely

Mucus may build up in the bladder substitute, which can lead to infection. You may need to use a catheter to irrigate, or flush out, the mucus periodically.

You may leak urine, particularly in the first 6 to 12 months after bladder substitute surgery. You can use disposable pads or briefs to absorb leaking urine. Urine leakage is especially common at night and, in some cases, continues beyond the first year after surgery.

Infection

Bacteria can enter urostomies and continent urinary diversions and may cause a urinary tract infection. Symptoms of infection include

- fever

- chills

- nausea

- vomiting

- poor appetite

- back or lower side pain

- frequent, painful urination

- cloudy, dark, or strong-smelling urine

If you have symptoms of an infection, see a health care professional right away.

Drink eight 8-ounce glasses of liquids each day—or more if recommended by your health care professional—to help prevent infection. Talk with your health care professional about urine testing and when to treat an infection.

Activities

Most people can return to their usual activities and exercises, including swimming and other water sports, once they have healed from urinary diversion surgery and regained their strength. You should avoid certain vigorous activities and heavy lifting after your surgery while your body heals.

Talk with your health care professional if your job is strenuous or requires heavy lifting, or if you play contact sports. Your health care professional may suggest that you adjust your job responsibilities, wear protective padding, or avoid certain activities that could harm your stoma.

Relationships

You may worry about how other people view your urinary diversion. Most people won’t know you’re wearing a pouch or have a urinary diversion unless you tell them. You can choose who to talk to and how much information to share.

Urinary diversion surgery may reduce sexual function; however, many people with a urinary diversion have satisfying sexual relationships. Your health care professional may suggest certain treatments, medicines, or therapy to help improve your sexual function. Talk with your health care professional about when it is safe for you to resume sexual activity, any pain you are having with sex, ways to protect the stoma, questions about intimacy, and any concerns you have about maintaining a healthy sexual relationship. It is also important to communicate openly with your partner about intimacy concerns.

Living with a urinary diversion requires some adjustment, and some people may feel discouraged or depressed after surgery. You may find it helpful to talk with a friend, family member, therapist, or support group about how you are feeling.

Will my diet need to change after urinary diversion?

Most people return to a normal diet after a urinary diversion. You may want to avoid certain foods that can cause urine to have a strong smell, such as asparagus and seafood, which may be noticeable when you empty the pouch. People with certain types of urinary diversion may not have enough vitamin B12 in their bodies and may need vitamin B injections. Talk with your health care professional about your dietary needs.

Clinical Trials for Urinary Diversion

The NIDDK conducts and supports clinical trials in many diseases and conditions, including urologic diseases. The trials look to find new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease and improve quality of life.

What are clinical trials for urinary diversion?

Clinical trials—and other types of clinical studies—are part of medical research and involve people like you. When you volunteer to take part in a clinical study, you help health care professionals and researchers learn more about disease and improve health care for people in the future.

Researchers are studying many aspects of urinary diversion, such as

- reducing complications after surgery

- improving postoperative care and reducing length of hospital stay

- surgical outcomes of robot-assisted surgery

Find out if clinical studies are right for you.

What clinical studies for urinary diversion are looking for participants?

You can view a filtered list of clinical studies on urinary diversion that are open and recruiting at www.ClinicalTrials.gov. You can expand or narrow the list to include clinical studies from industry, universities, and individuals; however, the NIH does not review these studies and cannot ensure they are safe. Always talk with your health care professional before you participate in a clinical study.

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Badrinath Konety, M.D., M.B.A., Rush University Medical College