Graves’ Disease

On this page:

- What is Graves’ disease?

- How common is Graves’ disease?

- Who is more likely to have Graves’ disease?

- What are the complications of Graves’ disease?

- What are the symptoms of Graves’ disease?

- What causes Graves’ disease?

- How do doctors diagnose Graves’ disease?

- How do doctors treat Graves’ disease?

- How do eating, diet, and nutrition affect Graves’ disease?

- Clinical Trials for Graves’ Disease

What is Graves’ disease?

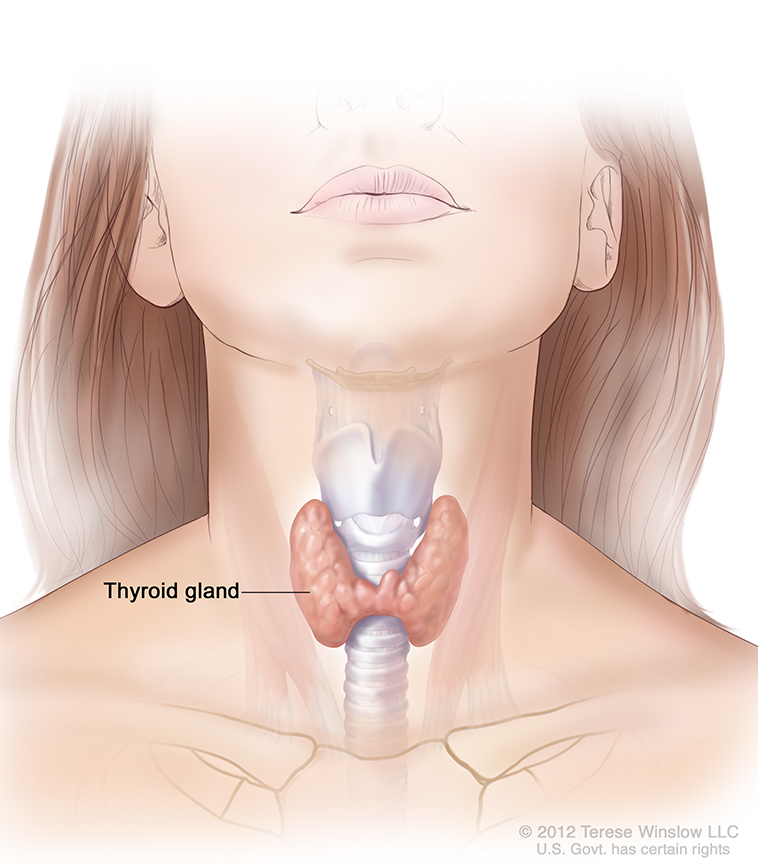

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder that can cause hyperthyroidism, or overactive thyroid. The thyroid is a small, butterfly-shaped gland in the front of your neck. Thyroid hormones control the way your body uses energy, so they affect nearly every organ in your body, even the way your heart beats.

With Graves’ disease, your immune system attacks your thyroid gland, causing it to make more thyroid hormones than your body needs. As a result, many of your body’s functions speed up.

How common is Graves’ disease?

Graves’ disease affects nearly 1 in 100 Americans.1 About 4 out of 5 cases of hyperthyroidism in the United States are caused by Graves’ disease.1

Who is more likely to have Graves’ disease?

Graves’ disease is more common in women and people older than age 30.2 You are more likely to develop the disease if you

- have a family history of Graves’ disease or Hashimoto’s disease

- have other autoimmune disorders, such as3,4

- vitiligo, which causes some parts of your skin to lose color

- autoimmune gastritis, which attacks the cells in your stomach lining

- type 1 diabetes, which occurs when your blood glucose, also called blood sugar, is too high

- rheumatoid arthritis, which affects your joints and sometimes other parts of your body

- use nicotine products

What are the complications of Graves’ disease?

Untreated, Graves’ disease can cause serious health problems, including

- a rapid and irregular heartbeat that can lead to blood clots, stroke, heart failure, and other heart-related problems

- thinning bones, osteoporosis, and muscle problems

- problems with the menstrual cycle, fertility, and pregnancy

- eye discomfort and changes in vision

What are the symptoms of Graves’ disease?

Graves’ disease often causes symptoms of hyperthyroidism. Graves’ disease can also affect your eyes and skin. Symptoms can come and go over time.

Hyperthyroidism

Symptoms of hyperthyroidism can vary from person to person and may include5

- weight loss, despite an increased appetite

- rapid or irregular heartbeat

- nervousness, irritability, trouble sleeping, fatigue

- shaky hands, muscle weakness

- sweating or trouble tolerating heat

- frequent bowel movements

- an enlarged thyroid gland, called a goiter

Symptoms of hyperthyroidism may include trouble sleeping and fatigue.

Symptoms of hyperthyroidism may include trouble sleeping and fatigue.

Eye problems

More than 1 in 3 people with Graves’ disease develop an eye disease called Graves’ ophthalmopathy (GO).6 GO occurs when your immune system attacks the muscles and other tissues around your eyes. Symptoms can include

- bulging eyes

- gritty, irritated eyes

- puffy eyes

- light sensitivity

- pressure or pain in the eyes

- blurred or double vision

These symptoms can start before or at the same time as symptoms of hyperthyroidism. Rarely, GO can develop after Graves’ disease has been treated. You can develop GO even if your thyroid function is normal. Most people have mild symptoms.

Skin problems

Rarely, people with Graves’ disease develop a condition that causes the skin to become reddish and thick, with a rough texture. Called Graves’ dermopathy or pretibial myxedema, the condition usually affects your shins but can also develop on the top of your feet and other parts of your body. Most cases are mild and painless.

What causes Graves’ disease?

Researchers aren’t sure why some people develop autoimmune disorders such as Graves’ disease. These disorders probably develop from a combination of genes and an outside trigger, such as a virus.

With Graves’ disease, your immune system makes an antibody called thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) that attaches to your thyroid cells. TSI acts like thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), a hormone made in your pituitary gland that tells your thyroid how much thyroid hormone to make. TSI causes your thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone.

How do doctors diagnose Graves’ disease?

Your doctor will take your medical history and perform a physical exam to look for signs of Graves’ disease. To confirm a diagnosis of Graves’ disease, your doctor may order one or more of these thyroid tests

-

Blood tests. These tests can measure the levels of your thyroid hormones and also check for TSI.

-

Radioactive iodine uptake test. This test measures the amount of iodine your thyroid is taking up from your bloodstream to make thyroid hormones. If your thyroid is taking up large amounts of iodine, you may have Graves’ disease.

-

Thyroid scan. This test, often done together with the radioactive iodine uptake test, shows how and where iodine is distributed in your thyroid. With Graves’ disease, the iodine shows up throughout the gland. With other causes of hyperthyroidism such as nodules—small lumps in the gland—the iodine shows up in a different pattern.

-

Doppler blood flow measurement. This test, also called Doppler ultrasound, uses sound waves to detect increased blood flow in your thyroid due to Graves’ disease. Your doctor may order this test if radioactive iodine uptake is not a good option for you, such as during pregnancy or breastfeeding.

How do doctors treat Graves’ disease?

Treating hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism is usually treated with medicines, radioiodine therapy, or thyroid surgery. Your doctor can help you identify the best option based on your age, health, symptoms, and other factors.

Beta-blockers. Beta-blockers are drugs that block the action of substances, such as adrenaline, on nerve cells. They cause blood vessels to relax and widen.

Antithyroid therapy is the easiest way to treat hyperthyroidism.

Antithyroid therapy is the easiest way to treat hyperthyroidism.-

Pros

- They can reduce symptoms—such as tremors, rapid heartbeat, and nervousness—until other treatments start working.

- They can make you feel better within hours.

-

Cons

- They don’t stop thyroid hormone production.

Antithyroid medicines. Antithyroid therapy is the simplest way to treat hyperthyroidism. Methimazole is used most often. Propylthiouracil is often used for women during the first 3 months of pregnancy because methimazole can, on rare occasions, harm the fetus.

- Pros

- They cause the thyroid to make less thyroid hormone.

- Some of your symptoms may go away temporarily after taking antithyroid drugs.

- Cons

- Antithyroid medicines can cause side effects, including

- allergic reactions, such as rashes and itching

- a decrease in the number of white blood cells in your body, which can lower resistance to infection

- liver failure, in rare cases

-

Antithyroid medicines

- may temporarily treat symptoms but are not a permanent cure for Graves’ disease

- may take several weeks or months for thyroid hormone levels to move into the normal range

- take about 1–2 years total average treatment time, but can continue for many years

- Antithyroid medicines can cause side effects, including

Seek care right away

While taking antithyroid drugs, call your doctor right away if you have any of the following symptoms

- fatigue or weakness

- dull pain in your abdomen

- loss of appetite

- skin rash, itching, or easy bruising

- yellowing of your skin or the whites of your eyes, called jaundice

- fever, chills, or constant sore throat

Radioiodine therapy is a common and effective treatment. You can take radioactive iodine-131 by mouth as a capsule or liquid.

- Pros

- Radioiodine therapy slowly destroys the cells of the thyroid gland that produce thyroid hormone.

- In the doses prescribed, radioiodine therapy does not affect other body tissues.

- Cons

- You might need more than one treatment to bring thyroid hormone levels into the normal range, but beta-blockers can control symptoms between treatments.

- Radioiodine therapy isn’t used for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. It can harm the fetus’ thyroid and can be passed from mother to child in breast milk.

- Radioiodine therapy may worsen symptoms of GO.

Almost everyone who gets radioiodine therapy later develops hypothyroidism. But hypothyroidism is easier to treat than hyperthyroidism by taking a daily thyroid hormone medicine, and it causes fewer long-term health problems.

Taking radioactive iodine-131 is a common and effective treatment.

Taking radioactive iodine-131 is a common and effective treatment.Surgery to remove part or most of the thyroid gland is used less often to treat hyperthyroidism. Sometimes doctors use surgery to treat people with large goiters or pregnant women who cannot take antithyroid medicines.

In some cases, doctors use surgery to remove part or most of the thyroid gland.

In some cases, doctors use surgery to remove part or most of the thyroid gland.- Pros

- When part of the thyroid is removed, your thyroid hormone levels may return to normal.

- Cons

- Thyroid surgery requires general anesthesia, which can lead to a condition called thyroid storm—a sudden, severe worsening of symptoms if antithyroid medicines are not taken before surgery to prevent this problem.

When part of your thyroid is removed, you may develop hypothyroidism after surgery and need to take thyroid hormone medicine. If your whole thyroid is removed, you will need to take thyroid hormone medicine for life. After surgery, your doctor will continue to check your thyroid hormone levels and will adjust your thyroid medicine dosage as needed.

Treating GO

Most cases of GO are mild. The following tips may help you control mild symptoms.

- Eye drops can help relieve dry, gritty, irritated eyes.

- If your eyelids do not fully close, taping them shut at night or wearing an eye mask can help prevent dry eyes.

- If you have puffy eyelids, sleeping with your head raised may reduce swelling.

- Sunglasses can help with light sensitivity.

- Special eyeglass lenses may help reduce double vision, if you have it.

Eye drops can relieve dry, gritty, irritated eyes.If you have severe GO, your doctor may recommend

Eye drops can relieve dry, gritty, irritated eyes.If you have severe GO, your doctor may recommend

- steroids or other medicines that reduce your body’s immune response

- surgery to improve bulging eyes or correct changes to your vision

- radiation therapy to the muscles and tissues around the eyes, used rarely

GO often improves with treatment or even resolves on its own. But it can come back or get worse. Triggers include stressful life events and smoking.6

Smoking makes GO worse. If you smoke or use other tobacco products, stop. Ask for help so you don’t have to do it alone. You can start by calling the National Quitline at 1-800-QUITNOW or 1-800-784-8669. For tips on quitting, go to Smokefree.gov.

How do eating, diet, and nutrition affect Graves’ disease?

Your thyroid uses iodine to make thyroid hormones. If you have Graves’ disease or another autoimmune thyroid disorder, you may be sensitive to harmful side effects from too much iodine in your diet. Eating foods that have large amounts of iodine—such as kelp, dulse, or other kinds of seaweed—may cause or worsen hyperthyroidism. Taking iodine supplements can have the same effect.

Talk with your health care professional about

- what foods to limit or avoid

- any iodine supplements you take

- any cough syrups or multivitamins you take, because some may contain iodine

Clinical Trials for Graves’ Disease

The NIDDK conducts and supports clinical trials in many diseases and conditions, including endocrine diseases. The trials look to find new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease and improve quality of life.

What are clinical trials for Graves’ disease?

Clinical trials—and other types of clinical studies—are part of medical research and involve people like you. When you volunteer to take part in a clinical study, you help doctors and researchers learn more about disease and improve health care for people in the future.

Researchers are studying many aspects of Graves’ disease, including new medicines for treating Graves’ disease and GO.

Watch a video of NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers explaining the importance of participating in clinical trials.

What clinical studies for Graves’ disease are looking for participants?

You can view a filtered list of clinical studies on Graves’ disease that are open and recruiting at ClinicalTrials.gov. You can expand or narrow the list to include clinical studies from industry, universities, and individuals; however, the National Institutes of Health does not review these studies and cannot ensure they are safe. Always talk with your health care provider before you participate in a clinical study.

References

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Leonard Wartofsky, M.D., M.A.C.P., Washington Hospital Center and Georgetown University Hospital