Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1

On this page:

- What is multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1?

- How common is MEN1?

- Who is more likely to develop MEN1?

- What are the complications of having MEN1?

- What are the symptoms of MEN1?

- What causes MEN1?

- How do doctors diagnose MEN1?

- How do doctors treat MEN1?

- How can genetic counseling help?

- Clinical Trials for MEN1

What is multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1?

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) is a rare genetic disorder that mainly affects the endocrine glands. Located in different parts of the body, these glands control the production of hormones that direct many body processes, including growth, digestion, and sexual function.

Previously called Wermer’s syndrome, MEN1 causes tumors to develop in the

- parathyroid glands

- pituitary gland

- pancreas and other parts of the digestive tract, such as the duodenum and stomach

People with MEN1 may also develop tumors—usually benign (not cancerous)—in other endocrine glands and body tissues, including the skin. Multiple tumors often develop at the same time in different tissues.

How common is MEN1?

MEN1 is a rare, inherited condition, occurring in about 1 in 30,000 people.1

Who is more likely to develop MEN1?

A family history of the disorder increases your risk. If one of your parents has the gene for MEN1, you have a 50 percent chance of inheriting the defective gene.

MEN1 affects men and women equally. Although the disorder can affect all age groups, the first symptoms are typically linked to overactive parathyroid glands and often appear in people in their early 20s.2,3 Most people are diagnosed as having MEN1 in their 40s, when the disorder has started to affect other endocrine glands.

What are the complications of having MEN1?

MEN1 causes tumors to develop in endocrine glands and other parts of the body. Although most of these tumors are noncancerous, they can cause the affected glands to increase in size and become overactive, producing too much hormone. In some cases, a large tumor may cause a gland to become underactive or unable to produce enough hormone.

Complications vary, depending on

- the location of the tumors

- the size of the tumors

- type of hormone(s) affected, if any

- whether or not the tumors are cancerous

Some tumors are nonfunctioning, which means they don’t produce hormones. When small, these tumors may not cause any complications.

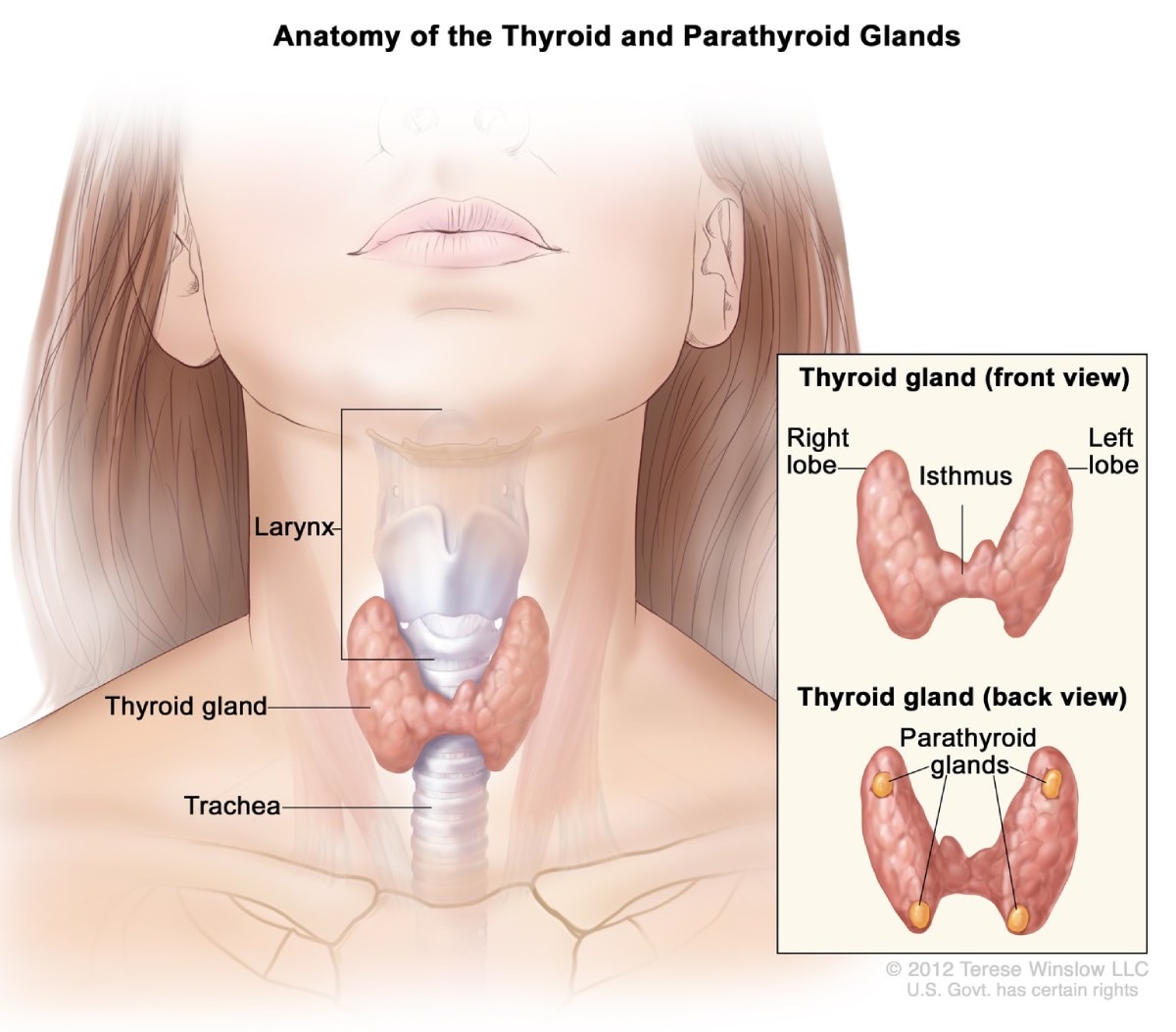

Parathyroid glands

About 95 percent of people with MEN1 develop tumors in the parathyroid glands by age 50.2 These four pea-sized glands produce parathyroid hormone, which helps maintain the right balance of calcium and phosphorus in your body. Over time, MEN1 can affect all four glands.

Hyperparathyroidism. MEN1-related tumors cause the parathyroid glands to become overactive, producing too much parathyroid hormone. This condition, called hyperparathyroidism, is the most common complication associated with MEN1. Excess parathyroid hormone causes calcium levels in your blood to rise too high. Complications can include bone loss and kidney stones.

Pancreas and digestive tract

About 40 percent of people with MEN1 develop cancers in the pancreas, duodenum, or other parts of the digestive tract.2 Many different types of small tumors may develop at the same time. Many of these tumors produce hormones, while others do not produce hormones. Some tumors may be cancerous.

In people with MEN1, the two most common tumors of the digestive tract are

- Gastrinomas. These tumors produce the hormone gastrin, which causes the stomach to release acid that helps the stomach digest food. Too much gastrin can cause stomach ulcers and serious diarrhea, leading to a condition called Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. People with MEN1 often have many small gastrinomas—most often in the duodenum but also in the pancreas. Over time, some of these tumors may become cancerous.

- Insulinomas. These tumors form only in the pancreas, in cells that produce the hormone insulin. Insulin controls levels of blood glucose (blood sugar) by moving glucose into the cells, where it can be used for energy. Insulinomas make too much insulin, leading to low blood sugar. These tumors are almost always noncancerous and can usually be removed with surgery.

Other, more rare pancreatic tumors may also develop and cause other complications. These tumors include

- Glucagonomas. These tumors cause cells in the pancreas to produce too much of the hormone glucagon, which raises blood sugar.

- VIPomas. These tumors cause cells in the pancreas to produce a hormone called vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), which releases water into the intestine.

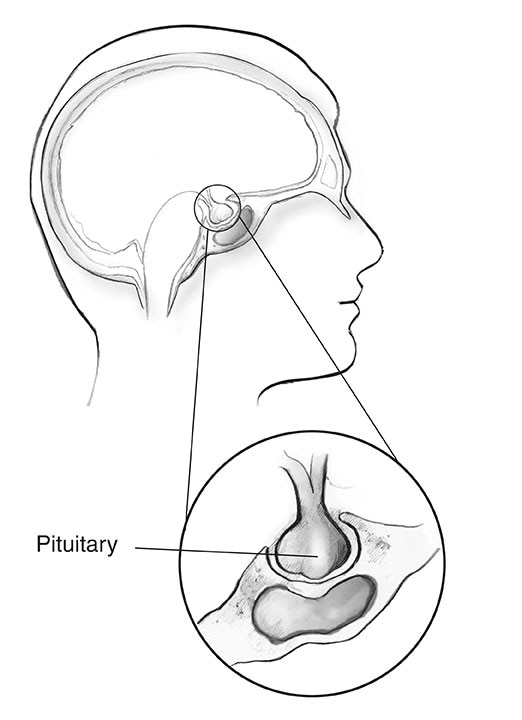

Pituitary gland

Nearly 1 in 3 people with MEN1 develop tumors in the front part of the pituitary gland, called the anterior lobe.2 Like other pituitary tumors, these growths are often small in size and are almost always benign.

In people with MEN1, the two most common pituitary tumors are

- Prolactinomas. The most common pituitary tumor in people with MEN1, prolactinomas produce the hormone prolactin. Normally, this hormone signals women’s breasts to produce milk during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Women with a prolactinoma may notice milk discharge from their breast(s) (called galactorrhea) when they are not pregnant or breastfeeding. Complications from having too much prolactin in the blood can include infertility and bone loss.

- Tumors that produce growth hormone (GH). GH-producing tumors are the second most common pituitary tumors in people with MEN1.4 Excess GH causes bones and other body tissues to grow larger in size, which can cause a condition called acromegaly. Related health problems can include arthritis, carpal tunnel syndrome, tumors of the colon or rectum, and heart disease.

Some tumors may produce both prolactin and GH. Other, more rare pituitary tumors may produce other hormones, which can lead to different symptoms and complications. These hormones include cortisol, which helps your body respond to stress, and thyroid hormones that affect metabolism.

Pituitary tumors that grow large in size may cause other problems, making it difficult for the pituitary gland to work properly. These tumors may prevent the pituitary gland from making enough hormones, leading to a condition called hypopituitarism. The tumors may also press against nearby brain tissues, causing headaches and/or vision problems.

Other tumors

MEN1 can also cause tumors in other parts of the body. Examples include

- tumors in other endocrine glands, such as the adrenal glands

- carcinoid tumors—slow-growing tumors most often found in the stomach, thymus, and lungs

- skin tumors and tumors under the skin, most commonly angiofibromas, lipomas (benign tumors made of fat cells), and collagenomas (tumors involving a protein in the skin called collagen)

- meningiomas and ependymomas—tumors of cells that line the brain and spinal cord

Complications may vary, depending on the type, size, and location of the tumor.

What are the symptoms of MEN1?

MEN1 symptoms can differ from person to person, even among family members who have the disorder. The age at which signs or symptoms appear may also vary.

Parathyroid tumors

As MEN1 almost always affects the parathyroid glands, the most common early symptoms are related to excess parathyroid hormone. These symptoms are often mild and may not be noticed for years. They include

- kidney stones

- muscle weakness

- tiredness

- increased thirst and urination

- depression

- aches and pains in bones and joints

- digestive problems and constipation

Other tumors

Tumors located in other endocrine glands can cause other symptoms, such as

- stomach ulcers

- acid reflux

- abdominal pain

- frequent diarrhea

- low blood glucose

- enlarged and swollen hands and feet

What causes MEN1?

MEN1 is an inherited disorder most often caused by a mutation in the MEN1 gene. The gene provides instructions for producing a protein called menin, known to play a role in keeping cells from growing and dividing too fast.

MEN1 is an autosomal dominant disorder. This means that only one parent needs to have the defective gene to pass the disorder on to a child. If one parent has the MEN1 gene, each child has a 1 in 2 (50%) chance of having the disorder. In about 1 in 10 cases, the mutation is not inherited from either parent but develops on its own. This is a natural, random process that can occur in anyone.4

Every person in the family who has MEN1 syndrome shares the same mutation. By studying different families with MEN1, scientists have identified hundreds of different mutations of the MEN1 gene that can cause the disorder. If you have any of these mutations, you are considered a carrier of MEN1, even if you have no symptoms.

Knowing if you are a carrier is important because, even without symptoms, you are very likely to develop some MEN1-related tumors in your lifetime. You may already have tumors developing that have not been detected if you have not had a thorough assessment, and you can still pass the disorder on to a child.

If there is a known MEN1 mutation in your family and genetic testing shows that you don’t carry it, then you don’t have MEN1 syndrome. You are unlikely to develop MEN1-related tumors in your lifetime and you won’t pass the disorder on to any children.

How do doctors diagnose MEN1?

Your doctor will diagnose you as having MEN1 if you meet one of these three criteria5

- two or more MEN1-related tumors (tumors in parathyroid glands, pituitary gland, and pancreas, or other part of the digestive tract)

- one MEN1-related tumor and a first-degree relative (a parent, brother or sister, or child) who has been clinically diagnosed as having MEN1

- a MEN1 mutation, even if you have no signs or symptoms of MEN1

Genetic testing for MEN1 mutation

Genetic testing will help you find out if you have a gene mutation known to cause MEN1. Testing is recommended for5

- people who have two or more MEN1-related endocrine tumors or other signs or symptoms of MEN1

- all first-degree relatives of a person who has the MEN1 gene mutation

An early diagnosis will help you monitor your symptoms and address problems before they become serious. Genetic testing for a known familial mutation may be appropriate starting as early as age 5 because, in rare cases, children with MEN1 may develop tumors of the pituitary or parathyroid glands. The typical age of onset for MEN1 syndrome is in the teens or 20s, but the first tumors in someone with MEN1 may develop earlier or later. The symptoms and types of tumors can differ even among members of the same family.

Genetic testing is most often performed on a blood sample. Some labs can also use saliva or a swab of the inside of the cheek to perform this testing.

In up to 1 in 4 cases, the test may not find a mutation even though you may be showing signs of the disorder.2 In these cases, the cause could be an unknown MEN1 mutation or a mutation in another gene. If your test doesn’t find a MEN1-related mutation, your doctor may order other tests to find out if your symptoms are due to another cause.

How do doctors treat MEN1?

Although MEN1 can’t be cured, most people with the disorder lead long and productive lives. Your doctor will monitor your health and provide treatment as needed.

Managing symptoms and monitoring tumors

Your doctor will monitor your symptoms and screen for the signs of MEN1-related tumors on a regular basis. Commonly used screening tests include

- Blood tests. These tests will help your doctor monitor levels of hormones and other substances linked to MEN1-related tumors. Examples include calcium and parathyroid hormone, prolactin, gastrin, and markers for certain tumors.

- Imaging tests. Your doctor may order imaging tests to monitor the size and growth of existing tumors and to detect new ones, including tumors that don’t release hormones or cause symptoms. These tests include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scan, and ultrasound. Other tests that look for abnormal hormone receptors—proteins that attach to certain hormones—on the surface of tumors can help detect tumors that may not be visible on an MRI or CT scan.

Based on your symptoms and test results, your doctor may prescribe different medicines to manage the progress of the disorder.

Treating tumors

If the tumors are small and not causing symptoms, no treatment may be needed. Doctors will follow these tumors with blood and imaging tests.

Treatment varies depending on the location and type of tumor. For example

- Parathyroid tumors are most often treated with surgery to remove the affected glands. If surgery is not possible, your doctor may prescribe medicines to control calcium levels.

- Tumors of the pancreas and digestive tract are often treated with medicines to control symptoms such as too much stomach acid. Other treatment options include surgery to remove the tumor(s), freezing or burning tumors that have spread to the liver without removing them, and, more rarely, systemic chemotherapy—treatment with anticancer drugs that travel through the blood to cells all over your body.

- Pituitary gland tumors are most often treated with medicines and/or surgery. Radiation therapy may also be used, but more rarely.

Treating multiple tumors. People with MEN1 often develop many tumors at the same time. As a result, treatment is more complicated than among people who have a single tumor or very few tumors. Sometimes, MEN1-related tumors may be larger, more aggressive, and resistant to treatment than other tumors.2

Surgery to remove tumors. Surgery is often successful in removing MEN1-related tumors and curing related symptoms. But in some cases, the tumors may grow back or spread to lymph nodes, the liver, or, more rarely, the bones. Your doctor may prescribe medicines to reduce the size of the tumor and treat related problems.

Postsurgery treatment. If a surgery removes an entire endocrine gland—or more than three parathyroid glands—your doctor may prescribe medicines to replace the hormones that your body is no longer making. You may also need to take other medicines and supplements, such as calcium and vitamin D, to address these deficiencies.

How can genetic counseling help?

Genetic counseling is a source of information and support to families affected by or at risk for a genetic disorder. For example, genetic counselors can help you and your family

- understand how genetic testing is done

- weigh the medical, social, financial, and ethical decisions involved in getting tested

- discuss available options on how to manage the disease

- make informed decisions regarding whether to have children and discuss options for testing a child, a fetus, or an embryo for a known familial mutation in MEN1

- find out which members of the family are at risk and might benefit from genetic testing for a known familial MEN1 mutation

Genetic counselors can also refer you to a range of support services, including education sources, advocacy and support groups, other health professionals, and local or state services.

You can find genetic counselors near you using the Find a Genetic Counselor search tool from the National Society for Genetic Counselors. When using the tool, under “Types of Specialization,” choose “Cancer.”

Clinical Trials for MEN1

The NIDDK conducts and supports clinical trials in many diseases and conditions, including endocrine diseases. The trials look to find new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease and improve quality of life.

What are clinical trials for MEN1?

Clinical trials—and other types of clinical studies—are part of medical research and involve people like you. When you volunteer to take part in a clinical study, you help doctors and researchers learn more about disease and improve health care for people in the future.

Researchers are studying many aspects of MEN1, including new treatments for this condition.

Find out if clinical studies are right for you.

What clinical studies for MEN1 are looking for participants?

You can view a filtered list of clinical studies on MEN1 that are open and recruiting at

ClinicalTrials.gov. You can expand or narrow the list to include clinical studies from industry, universities, and individuals; however, the National Institutes of Health does not review these studies and cannot ensure they are safe. Always talk with your health care provider before you participate in a clinical study.

References

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Roland W. Stein, M.D., Vanderbilt University