Anatomic Problems of the Lower GI Tract

- About the Lower GI Tract

- Anorectal Malformations (Imperforate Anus)

- Colonic Atresia & Stenosis

- Malrotation

- Intussusception

- Colonic & Anorectal Fistulas

- Rectal Prolapse

- Colonic Volvulus

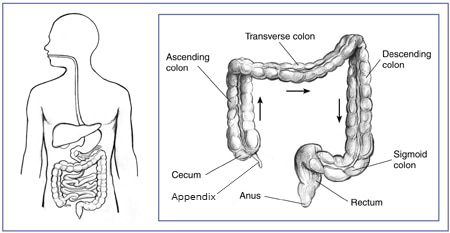

About the Lower GI Tract

What is the lower GI tract?

The lower gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the last part of the digestive tract. The lower GI tract consists of the large intestine and the anus.

The large intestine absorbs water and changes the waste products of the digestive process from liquid into formed stool. The large intestine includes

- the appendix, a finger-shaped pouch attached to the cecum

- the cecum, the first part of the large intestine, which is connected to the end of the small intestine

- the colon, which has four sections: the ascending colon, the transverse colon, the descending colon, and the sigmoid colon

- the rectum, the lower end of the large intestine leading to the anus

The anus is a 1-inch opening at the end of your digestive tract through which stool leaves your body. The anus includes the sphincter muscles—muscles that open and close and allow you to control bowel movements.

What are anatomic problems of the lower GI tract?

Anatomic problems of the lower GI tract are problems related to the structure of the lower GI tract. The parts of the lower GI tract may be in the wrong place, may not be shaped normally, or may not connect normally to other parts of the body.

Some anatomic problems of the lower GI tract arise when the lower GI tract does not develop normally before birth. These are called birth defects and include

Other anatomic problems, which might be present at birth or develop later, include

Anorectal Malformations (Imperforate Anus)

What are anorectal malformations?

Anorectal malformations are birth defects of a child’s anus or rectum that interfere with the normal passage of stool. When the anus is completely blocked, the condition is called imperforate anus.

In children with anorectal malformations, the anus may be missing, blocked by a thin or thick layer of tissue, or more narrow than normal. In rare cases, the anus may be normal while the rectum is blocked or narrowed.

Many children with anorectal malformations have a fistula, or abnormal passage, between the rectum to another part of the body, such as the

In some children with anorectal malformations, the rectum and the urinary tract have the same opening. This abnormality is called a cloaca.

How common are anorectal malformations?

About 1 in every 5,000 babies is born with anorectal malformations.1

Who is more likely to be born with anorectal malformations?

Boys are slightly more likely than girls to be born with anorectal malformations.1

If parents have one child with an anorectal malformation, the chance that a future child will have the condition is 1 in 100, which is higher than the average risk of 1 in 5,000.1

What other health problems do children with anorectal malformations have?

Children with anorectal malformations may have birth defects that affect other parts of the body. These may include defects of the

- urinary tract and sex organs

- heart

- spine

- gastrointestinal (GI) tract

- trachea, also called the windpipe

- kidneys

- arms and legs

In some cases, children with Down syndrome also have anorectal malformations.

What are the complications of anorectal malformations?

If anorectal malformations are not diagnosed and treated shortly after a baby is born, the baby may develop symptoms of intestinal obstruction, such as vomiting, bloating or visible swelling of the abdomen, and not being able to pass stool. Intestinal obstruction can lead to serious complications, such as a hole in the wall of the intestine called a perforation, serious infection, and sepsis.

After anorectal malformations have been treated with surgery, some people may have complications later in life such as

- constipation

- bowel control problems

- bladder control problems

- problems with sexual function

What are the signs of anorectal malformations?

When examining a newborn baby, doctors may find signs of anorectal malformations, such as

- no visible anus

- an anal opening that is not in the normal location

- an anus that is tighter or more narrow than normal

In the first 24 hours after birth, babies with anorectal malformations may pass no stool or may pass stool through a fistula and out of the perineum, urethra, or vagina.

Babies with signs of anorectal malformation need medical treatment right away to prevent complications.

What causes anorectal malformations?

Anorectal malformations occur when the anus and rectum don’t develop normally before birth. Experts don’t know what causes problems with the development of the anus and rectum. However, genes or changes in genes—called mutations—may play a role.

How do doctors diagnose anorectal malformations?

Doctors diagnose anorectal malformations with a physical exam and imaging tests. They may also order tests to check for other health problems that are common in children with anorectal malformations.

Physical exam

Shortly after a baby is born, a doctor will examine the baby from head to toe. Doctors often diagnose anorectal malformations during this exam. Doctors will also examine the baby’s perineum and genitals and check for other birth defects.

Imaging tests

Doctors may use the following tests to examine defects of the anus and rectum

- ultrasound, which uses sound waves to create an image of organs

- x-rays, which use a small amount of radiation to create pictures of the inside of the body

- magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which takes pictures of the body’s internal organs and soft tissues without using x-rays

How do doctors treat anorectal malformations?

Doctors treat anorectal malformations with surgery. The type of surgery depends on the location and type of malformation.

Doctors often perform surgery in the first few days after the baby is born. In some cases, doctors can repair the anorectal malformation with one operation. In other cases, doctors first perform a colostomy to attach the colon to a stoma, an opening in the abdomen that allows stool to exit the body. Then doctors repair the anorectal malformation with one or more operations when the baby is older.

Doctors may recommend regular follow-up care and additional treatments for any complications that develop after surgery or later in life.

Reference

Colonic Atresia & Stenosis

What are colonic atresia and stenosis?

Colonic atresia is a birth defect in which part of the colon is completely blocked or missing. Colonic stenosis, which may be a birth defect or may develop later in life, is a condition in which part of the colon is more narrow than normal.

How common are colonic atresia and stenosis?

About 1 in every 10,000 to 66,000 babies is born with colonic atresia.2

Experts don’t know how common colonic stenosis is. At birth, colonic stenosis is rarer than colonic atresia.3 Most cases of colonic stenosis develop later in life and are caused by injury or inflammation.

Who is more likely to get colonic atresia and stenosis?

Experts don’t know who is more likely to have colonic atresia and stenosis at birth.

People are more likely to develop colonic stenosis later in life if they have an injury or inflammation of the colon that may cause stenosis.

Premature babies might develop colonic stenosis after having necrotizing enterocolitis, a condition in which the wall of the intestine suffers serious damage.

What other health problems do babies born with colonic atresia have?

Babies born with colonic atresia may have other birth defects, including

- atresia in the small intestine

- defects of the wall of the abdomen

- Hirschsprung disease

- malrotation

What are the complications of colonic atresia and stenosis?

Colonic atresia causes intestinal obstruction, in which the colon is completely blocked. If colonic atresia is not diagnosed and treated shortly after a baby is born, intestinal obstruction can lead to serious complications such as

- dehydration

- a perforation, or hole, in the wall of the intestine

- infection and sepsis, a serious illness that occurs when the body has an overwhelming immune system response to an infection

Colonic stenosis can also cause intestinal obstruction and its complications.

What are the signs and symptoms of colonic atresia and stenosis?

Colonic atresia and stenosis may cause signs and symptoms due to intestinal obstruction. Anyone with signs or symptoms of intestinal obstruction needs medical help right away.

Signs of intestinal obstruction due to colonic atresia include

- bloating or visible swelling of the abdomen

- passing no stool

- vomiting, often with bile in the vomit, which makes it green in color

These signs typically appear in babies soon after birth.

Colonic stenosis can also cause intestinal obstruction, and signs and symptoms may be similar to those of colonic atresia. Signs and symptoms may be milder or may come and go if the colon is not completely blocked.

What causes colonic atresia and stenosis?

Experts aren’t sure what causes colonic atresia and stenosis to occur as birth defects. One theory is that before birth, something happens to reduce the flow of blood to part of the colon.

Injury or inflammation of the colon may cause colonic stenosis at any time during a person’s life. For example, necrotizing enterocolitis is a common cause of colonic stenosis in babies. Later in life, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as Crohn’s disease, is a cause of colonic stenosis, also called a stricture.

How do doctors diagnose colonic atresia and stenosis?

To diagnose colonic atresia and stenosis, doctors ask about symptoms and medical history and perform a physical exam and imaging tests.

Physical exam

During a physical exam, the doctor may

- check for bloating of the abdomen

- check for a lump or mass in the abdomen

- press or tap on the abdomen to check for tenderness or pain

- use a stethoscope to listen to sounds in the abdomen

- check for signs of complications, such as dehydration or infection

Imaging tests

Doctors may use the following tests to diagnose colonic atresia and stenosis

- x-rays, which use a small amount of radiation to create pictures of the inside of the body

- ultrasound, which uses sound waves to create an image of organs

- lower GI series, which uses x-rays and a chalky liquid called barium to view the large intestine

How do doctors treat colonic atresia and stenosis?

Doctors treat colonic atresia and stenosis with surgery to remove the blocked or narrowed part of the colon and attach the healthy ends of the colon to each other.

In some cases, doctors treat colonic atresia or stenosis with one operation. In other cases, doctors first perform a colostomy to attach the colon to a stoma, an opening in the abdomen that allows stool to exit the body. Later, doctors perform a second operation to attach the healthy ends of the colon to each other.

References

Malrotation

What is malrotation?

Malrotation is a birth defect that occurs when the intestines do not correctly or completely rotate into their normal final position during development. People born with malrotation may develop symptoms and complications, most often when they are babies but sometimes later in life. Some people with malrotation never develop symptoms or complications.

How common is malrotation?

Experts are not sure how common malrotation is because not all people with malrotation develop signs or symptoms. Some studies suggest that about 1 in 500 people have malrotation.4

Who is more likely to get malrotation?

Malrotation is most commonly diagnosed in babies. Up to 80 percent of babies with malrotation are diagnosed in the first month of life.5,6

What other health problems do people with malrotation have?

Children with malrotation may have other birth defects, including defects of the

- gastrointestinal (GI) tract

- wall of the abdomen

- heart

- biliary tract

- pancreas

What are the complications of malrotation?

Malrotation can cause volvulus, or twisting, of the small intestine. Malrotation can also cause intestinal obstruction due to bands of mesentery—the tissues that hold the intestines in place—pressing against the duodenum. These problems can lead to serious and life-threatening complications such as

- lack of blood flow to the blocked part of the intestine and death of the blood-starved tissues

- a perforation, or hole, in the wall of the intestine

- peritonitis, an infection of the lining of the abdominal cavity

- sepsis, a serious illness that occurs when the body has an overwhelming immune system response to an infection

- shock

What are the symptoms of malrotation?

If you or your child has signs or symptoms of malrotation or its complications, you should seek medical help right away.

Common signs of malrotation in babies younger than age 1 include7

- vomiting, often with bile in the vomit, which makes it green in color

- failure to thrive

- pain or tenderness in the abdomen

- bloating of the abdomen

- bleeding from the rectum or passing bloody stools

In children older than age 1 and adults, common signs and symptoms include7

- pain in the abdomen

- vomiting

- nausea

- diarrhea

- bloating

- constipation

- bleeding from the rectum or passing bloody stools

- failure to thrive in children

If malrotation and its complications cut off blood flow to the intestines and cause shock, symptoms may include

- confusion or unconsciousness

- fast heart rate

- pale skin

- sweating

What causes malrotation?

Experts don’t know what causes malrotation. However, genes or changes in genes—called mutations—may play a role.

How do doctors diagnose malrotation?

Doctors diagnose malrotation based on medical and family history, a physical exam, and imaging tests.

Physical exam

During a physical exam, a doctor will check for signs of pain, tenderness, or bloating or visible swelling of the abdomen and may listen to sounds inside the abdomen using a stethoscope. A doctor may also check for signs of shock, such as a rapid pulse or low blood pressure.

Imaging tests

Doctors may use the following imaging tests to diagnose malrotation

- x-rays, which use a small amount of radiation to create pictures of the inside of the body

- lower GI series, which uses x-rays and a chalky liquid called barium to view the large intestine

- upper GI series, which uses x-rays and barium to view the upper GI tract, including the small intestine

- ultrasound, which uses sound waves to create an image of organs

How do doctors treat malrotation?

Doctors treat malrotation and its complications with surgery. During surgery, the surgeon may

- divide any bands of tissue in the abdomen that are causing complications or might in the future

- change the position of the intestines to lower the risk of future complications

- untwist any volvulus

- remove any parts of the intestines damaged by volvulus

- remove the appendix, since malrotation can make it difficult to diagnose appendicitis if the patient develops this condition in the future

References

Intussusception

What is intussusception?

Intussusception is a condition in which part of the intestine folds into itself, much like a collapsible telescope. Usually, the last part of the small intestine, called the ileum, folds into the first part of large intestine, called the cecum.

How common is intussusception?

In the United States, about 35 to 40 of every 100,000 babies younger than age 1 is hospitalized for intussusception.8 Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in babies and young children.9,10

Who is more likely to get intussusception?

Babies and young children are more likely than adults to get intussusception. Intussusception is most common in babies younger than age 1, and about 90 percent of cases occur in children younger than age 3.11

Intussusception is rare in adults. Only about 5 percent of cases of intussusception occur in adults.11

Intussusception is more common in boys than in girls.11

What are the complications of intussusception?

Without treatment, intussusception can lead to life-threatening complications, such as

- intestinal obstruction

- dehydration

- lack of blood flow to the blocked part of the intestine and death of the blood-starved tissues

- a perforation, or hole, in the wall of the intestine

- peritonitis, an infection of the lining of the abdominal cavity

- sepsis, a serious illness that occurs when the body has an overwhelming immune system response to an infection

- shock

What are the symptoms of intussusception?

Anyone with signs or symptoms of intussusception or its complications should get medical help right away.

The signs and symptoms of intussusception in babies and children may include

- severe colicky or crampy pain in the abdomen

- crying and not able to be comforted

- drawing their knees up to their chest

- lethargy, or lack of energy

- vomiting

- stool mixed with blood and mucus, called currant jelly stool

Symptoms of intussusception in adults may include

- pain in the abdomen

- nausea

- vomiting

- bleeding from the rectum or blood in the stool

- constipation

- bloating

Signs and symptoms of complications of intussusception may include

- signs of dehydration, such as thirst, urinating less than usual, and feeling tired

- signs of infection, such as fever

- signs of shock, such as confusion or unconsciousness, a fast heart rate, pale skin, and sweating

What causes intussusception?

Children

In most cases of intussusception in babies and young children, doctors cannot find a cause. Research suggests that infections with viruses or bacteria may increase the chance of intussusception.

Doctors can find a cause in only 2 to 12 percent of cases of intussusception in children.11 These causes include

- abnormal growths in the intestines, such as benign or cancerous tumors, polyps, or cysts

- birth defects in the digestive tract, such as malrotation and Meckel’s diverticulum

- diseases and disorders such as cystic fibrosis, IgA vasculitis, and hemophilia

- surgery

Adults

In adults, doctors can find the cause of intussusception in about 90 percent of cases.12 Causes of intussusception in adults include

- abnormal growths in the intestines, such as benign and cancerous tumors and polyps

- abdominal adhesions that form after surgery

- diseases such as cystic fibrosis, celiac disease, and Crohn’s disease

How do doctors diagnose intussusception?

To diagnose intussusception, doctors will ask about symptoms and medical history, perform a physical exam, and order imaging tests.

Physical exam

During a physical exam, the doctor may

- check for bloating of the abdomen

- check for a lump or mass in the abdomen

- press or tap on the abdomen to check for tenderness or pain

- use a stethoscope to listen to sounds in the abdomen

- check for signs of complications, such as dehydration or shock

Imaging tests

Doctors may use the following tests to diagnose intussusception

- x-rays, which use a small amount of radiation to create pictures of the inside of the body

- ultrasound, which uses sound waves to create an image of organs

- lower GI series, which uses x-rays and a chalky liquid called barium to view the large intestine

- computed tomography (CT), more commonly used in adults, which uses a combination of x-rays and computer technology to create images

How do doctors treat intussusception?

In babies and children, doctors most often treat intussusception by performing an enema procedure that is similar to a lower GI series. A doctor inserts a tube through the anus and, with x-ray guidance, fills the large intestine with air, barium, or another substance to push the telescoped intestine back to its normal position.

A doctor may need to perform surgery to treat intussusception if the enema procedure does not work. A doctor may also perform surgery if the cause or complications of intussusception need treatment.

In adults, doctors most often treat intussusception with surgery.

References

Colonic & Anorectal Fistulas

What are colonic and anorectal fistulas?

A fistula is an abnormal passageway, or tunnel, in the body. An internal fistula is an abnormal tunnel between two internal organs. An external fistula is an abnormal tunnel between an internal organ and the outside of the body.

A colonic fistula is an abnormal tunnel from the colon to the surface of the skin or to an internal organ, such as the bladder, small intestine, or vagina.

An anorectal fistula is an abnormal tunnel from the anus or rectum to the surface of the skin around the anus. Women may have rectovaginal fistulas, which are anorectal fistulas between the anus or rectum and the vagina.

How common are colonic and anorectal fistulas?

Colonic fistulas are rare and may occur as a complication of surgery or of a condition such as diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease, or cancer.

Studies conducted in Europe have found that about 1 or 2 in every 10,000 people have anorectal fistulas.13 Anyone can get an anorectal fistula, which usually starts as an infection in a gland inside the anus. Anorectal fistulas are more likely to occur in people who have had an anorectal abscess and in people with Crohn’s disease.

Anorectal fistulas are more common in men than in women. While anorectal fistulas can occur in people of any age, the average age of people with anorectal fistulas is about 40.13,14

What are the complications of colonic and anorectal fistulas?

Colonic fistula

Colonic fistulas can cause complications such as

- problems with the fluid and electrolyte balance in your body, such as dehydration or low levels of certain electrolytes

- malnutrition

- infections, such as urinary tract infections

- peritonitis, an infection of the lining of the abdominal cavity

- abscesses, which are painful, swollen, pus-filled areas caused by infections

- sepsis, a serious illness that occurs when your body has an overwhelming immune system response to an infection

Anorectal fistula

Anorectal fistulas cause infections and abscesses around the anus, but they rarely cause severe infection. In rare cases, cancer may develop in an anorectal fistula.

What are the symptoms of colonic and anorectal fistulas?

You should see a doctor if you have any symptoms of a colonic or anorectal fistula.

Colonic fistula

Symptoms of colonic fistula vary, depending on the location of the fistula. The contents of the colon may enter the fistula and pass to the other end, which may be in the skin or in an internal organ.

Symptoms of colonic fistula may include fluid, stool, and gas passing

- through an opening in the skin

- in the urine

- through the vagina

A fistula that connects the colon to another part of the intestines may cause symptoms such as

In some cases, colonic fistulas do not cause symptoms.

Anorectal fistula

Symptoms of an anorectal fistula may include

- drainage of pus from an opening in the skin around the anus

- swelling and pain near the anus that may come and go, sometimes with redness or fever

- anal pain

In women, a rectovaginal fistula may cause symptoms such as the passage of stool or gas through the vagina.

What causes colonic and anorectal fistulas?

Most colonic and anorectal fistulas are acquired, meaning that they are not present at birth and develop at some point in a person’s life.

Colonic fistula

The most common cause of colonic fistulas is abdominal surgery. Diseases that cause inflammation of the GI tract, such Crohn’s disease and diverticular disease, can also cause fistulas to form. Other causes include cancer, radiation therapy, and trauma or injury to the abdomen.

Anorectal fistula

Anorectal abscesses, caused by infections of the anal glands, are the most common cause of anorectal fistulas.

Certain health problems may also cause anorectal fistulas, including Crohn’s disease, cancer, and some infections such as tuberculosis and HIV. Damage to the anorectal area due to surgery, childbirth, injury, or radiation therapy may also cause anorectal fistulas.

How do doctors diagnose colonic and anorectal fistulas?

Doctors diagnose colonic and anorectal fistulas based on symptoms and medical history, a physical exam, and imaging tests.

Medical history

Your doctor will ask about your symptoms and history of conditions that may cause fistulas, such as abdominal surgery, Crohn’s disease, diverticular disease, radiation therapy, or injury.

Physical exam

Your doctor will check for tenderness or pain in your abdomen and may listen to sounds inside your abdomen using a stethoscope. Your doctor will examine any opening in your skin to determine if you may have an external colonic fistula.

To check for an anorectal fistula, your doctor will check the skin around your anus for abnormal openings, pain, and signs of inflammation or infection. Your doctor may perform a digital rectal exam and may perform an anoscopy or a proctoscopy to view the inside of the anus and rectum.

Imaging tests

Doctors may use several different imaging tests to diagnose or examine colonic or anorectal fistulas. The type of test depends on the suspected location of the fistula. Tests may include

- ultrasound, which uses sound waves to create an image of your organs

- lower GI series, which uses x-rays and a chalky liquid called barium to view your large intestine

- computed tomography (CT) scans, which use a combination of x-rays and computer technology to create images

- magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which takes pictures of your body’s internal organs and soft tissues without using x-rays

- fistulography, which involves taking x-rays after injecting contrast media into a fistula to help it show up more clearly on the x-rays

Doctors may order additional tests to check for complications or to diagnose conditions that can cause fistulas, such as Crohn’s disease or cancer. If a fistula connects to an internal organ, such as the bladder, small intestine, or vagina, doctors may order additional tests to examine these organs.

How do doctors treat colonic and anorectal fistulas?

Colonic fistula

Some colonic fistulas will close on their own without surgery. Your doctor may only treat or prevent any complications to help the fistula heal. Depending on your needs, your doctor may

- give you fluids and electrolytes

- give you nutritional support, which may include total parenteral nutrition (TPN), which is intravenous (IV) nutrition, or enteral nutrition, in which you receive liquid food through a tube placed in your nose, stomach, or small intestine

- prescribe antibiotics and drain any abscesses to treat infection

- protect your skin from the fluid draining from the fistula if you have an external fistula

If a fistula is not likely to close on its own, doctors perform surgery to close the fistula.

Anorectal fistula

Doctors typically treat anorectal fistulas with surgery. Most anorectal fistulas won’t close on their own without surgery, but some rectovaginal fistulas may close on their own. If you have a rectovaginal fistula, your doctor may recommend delaying surgery to see if the fistula will close.

If you have an anorectal fistula with an abscess, your doctor will drain the abscess to treat the infection. In some cases, doctors may prescribe antibiotics to treat the infection.

References

Rectal Prolapse

What is rectal prolapse?

Rectal prolapse occurs when the rectum drops down through the anus. In complete rectal prolapse, the entire wall of the rectum drops through the anus. In partial rectal prolapse, only the lining of the rectum drops through the anus.

How common is rectal prolapse?

Rectal prolapse is relatively uncommon. A study conducted in Finland found that, each year, about 2.5 out of every 100,000 people are diagnosed with complete rectal prolapse.15

Who is more likely to get rectal prolapse?

Among adults, rectal prolapse is more common in those older than age 50 and more common in women than in men. About 80 to 90 percent of adults with rectal prolapse are women.16

Rectal prolapse is rare in children, and children with this condition are typically younger than age 4.17

What other health problems do people with rectal prolapse have?

Some women who have rectal prolapse have weak pelvic floor muscles. These women may have other problems related to weak pelvic floor muscles, such as

- a hernia of the intestines, called an enterocele

- bulging of the rectum into the front of the vagina, called rectocele

- bulging or dropping of the bladder into the vagina, called cystocele

- dropping of the uterus or vagina out of their normal positions, called uterine or vaginal prolapse

What are the complications of rectal prolapse?

The complications of rectal prolapse include

- ulcers in the rectum, which may cause bleeding

- a rectal prolapse that can’t be pushed back inside the body, which is a medical emergency because it can cut off the blood supply to the part of the rectum that has dropped through the anus

- damage to the sphincter muscles and nerves, causing or worsening bowel control problems (fecal incontinence)

What are the symptoms of rectal prolapse?

The symptoms of rectal prolapse include

- a reddish-colored mass that sticks out of the anus

- constipation or diarrhea or both

- feeling that the rectum is not empty after a bowel movement

- passing blood and mucus from the rectum

- fecal incontinence

Without treatment, symptoms such as constipation and bowel control problems may get worse. Over time, the rectum may drop through the anus more often and more easily. The rectum may not go back inside the body on its own and may need to be pushed back into place.

If you have symptoms of rectal prolapse, you should see a doctor for treatment. Treatment can help prevent symptoms from getting worse and prevent complications.

Seek medical help right away if you have symptoms of complications, such as heavy bleeding or a rectal prolapse that can’t be pushed back inside the body.

What causes rectal prolapse?

Experts aren’t sure what causes rectal prolapse. Certain structural defects and risk factors may increase the chance of rectal prolapse.

Structural defects

In adults with rectal prolapse, doctors have found certain defects in the pelvis or lower GI tract. These defects may increase the chance of rectal prolapse, or rectal prolapse may cause or worsen these defects. Structural defects often found in adults with rectal prolapse include

- a rectum that is not fixed in place and is able to move more than normal

- weak pelvic floor muscles

- weak anal sphincters

In children with rectal prolapse, doctors have found differences in the structure of the rectum. For example, the rectum may not have the usual curve and may be in a straight, vertical position, which may increase the chance of prolapse.

Risk factors

Certain conditions that increase pressure inside the abdomen or weaken the pelvic floor muscles may increase the chance of rectal prolapse. Examples include

- chronic constipation or straining during bowel movements

- chronic diarrhea

- cystic fibrosis

- diseases and disorders that affect the nerves or tissues of the pelvic floor muscle

- intestinal infections with certain parasites

- pelvic surgery

- whooping cough

How do doctors diagnose rectal prolapse?

To diagnose rectal prolapse, doctors ask about medical history and symptoms and perform a physical exam. In some cases, doctors also order tests.

Physical exam

Your doctor will examine your anus to see if you have a complete or partial rectal prolapse. If your doctor doesn’t see a prolapse, he or she may ask you to strain as if you are having a bowel movement to see the rectal prolapse. Your doctor may also perform a digital rectal exam.

Tests

Doctors may order tests to confirm the diagnosis of rectal prolapse or to check for other problems. These tests may include

- defecography, which uses x-rays or magnetic resonance imaging to create a video that shows how well your rectum can hold and empty stool and shows structural changes in your rectum and anus

- colonoscopy, which uses a long, flexible, narrow tube with a light and tiny camera on one end, to look inside your rectum and entire colon

- lower GI series, which uses x-rays and a chalky liquid called barium to view your large intestine

Doctors may order additional tests to check how well the nerves and muscles of your rectum and anus are working, such as anorectal manometry.

How do doctors treat rectal prolapse?

In adults, doctors most often treat rectal prolapse with surgery. Even after surgery, rectal prolapse can happen again. Reducing or avoiding constipation can lower the chance that it will happen again.

In children, doctors typically treat rectal prolapse by treating the underlying cause, such as constipation, straining during bowel movements, or diarrhea. If treating the cause doesn’t work, doctors may perform surgery to correct the prolapse.

References

Colonic Volvulus

What is colonic volvulus?

Colonic volvulus occurs when the colon twists around the tissue that holds it in place, called mesentery. The twisting causes intestinal obstruction.

The most common types of colonic volvulus are

- sigmoid volvulus, which is twisting of the sigmoid colon

- cecal volvulus, which is twisting of the cecum and ascending colon

How common is colonic volvulus?

Colonic volvulus is uncommon in the United States, causing less than 5 of every 100 cases of intestinal obstruction.18

Colonic volvulus is more common in Africa, the Middle East, India, Russia, Eastern Europe, and South America. In these regions, colonic volvulus causes 13 to 42 of every 100 cases of intestinal obstruction.18 Experts think this condition is more common because people in these regions are more likely to eat a high-fiber diet, which is a risk factor for colonic volvulus.19

Who is more likely to get colonic volvulus?

Colonic volvulus is most common in adults between the ages of 50 and 80. Sigmoid volvulus is more common in men, while cecal volvulus is more common in women.20

Sigmoid volvulus is more common in older adults who

- have chronic constipation

- have mental health or nervous system disorders

- have chronic medical conditions

- live in nursing homes or psychiatric facilities

What are the complications of colonic volvulus?

Colonic volvulus can cause life-threatening complications. The twisting of the colon can lead to

- intestinal obstruction

- dehydration

- lack of blood flow to the blocked part of the colon and death of the blood-starved tissues

- a perforation, or hole, in the wall of the intestine

- peritonitis, an infection of the lining of the abdominal cavity

- sepsis, a serious illness that occurs when the body has an overwhelming immune system response to an infection

- shock

What are the symptoms of colonic volvulus?

If you have symptoms of colonic volvulus or its complications, seek medical help right away.

Symptoms of colonic volvulus may include

Symptoms of complications of colonic volvulus may include

- symptoms of infection, such as fever

- symptoms of shock, such as confusion or unconsciousness, a fast heart rate, pale skin, and sweating

What causes colonic volvulus?

Certain structural differences and risk factors may increase the chance of colonic volvulus.

Structural differences

Experts think that certain structural differences in the cecum and colon increase the chance of volvulus. For example

- the sigmoid colon may be longer than average

- the tissue that holds the sigmoid colon in place may allow it to move more than usual

- the cecum and the ascending colon may not be fixed in place and may move more than usual

Risk factors

The chance of colonic volvulus may be higher in people with certain conditions, such as

Sigmoid volvulus is more common in older adults who have chronic medical conditions or disorders that involve the nervous system and mental health. Sigmoid volvulus is also more common among older adults who live in nursing homes or psychiatric facilities and spend long periods of time in bed.

In children, diseases such as Hirschsprung disease or Chagas disease can cause severe swelling of the colon, called megacolon, which can lead to volvulus.

The chance of cecal volvulus is higher in people who have had colonoscopy or laparoscopy and in women who are pregnant.

How do doctors diagnose colonic volvulus?

Your doctor will diagnose volvulus of the colon based on your symptoms and medical history, a physical exam, and medical tests.

Medical history

Your doctor will ask about your symptoms and any history of conditions that may be risk factors for colonic volvulus.

Physical exam

During a physical exam, your doctor may

- check for bloating of your abdomen

- press or tap on your abdomen to check for tenderness or pain

- use a stethoscope to listen to sounds within your abdomen

- check for signs of complications, such as infection or shock

Imaging tests

Doctors may use one or more imaging tests to check for volvulus of the colon. These tests may include

- x-rays, which use a small amount of radiation to create pictures of the inside of your body

- computed tomography (CT), which uses a combination of x-rays and computer technology to create images

- lower GI series, which uses x-rays and a chalky liquid called barium to view your large intestine

How do doctors treat colonic volvulus?

Doctors most often treat colonic volvulus with surgery.

Sigmoid volvulus

If you don’t have signs of damage to your colon, your doctor may use flexible sigmoidoscopy to examine your sigmoid colon and try to untwist the volvulus. If the procedure is successful, the doctor may plan surgery to remove the affected part of your colon. This surgery can prevent the volvulus from happening again. You typically have the flexible sigmoidoscopy and surgery during the same hospital stay.

If your colon is damaged or if the doctor can’t untwist the volvulus during flexible sigmoidoscopy, you will need surgery right away to remove the affected part of the colon.

Cecal volvulus

Doctors treat cecal volvulus with surgery. Most often, doctors will remove the affected part of the cecum and colon. In some cases, doctors may perform surgery to untwist the volvulus and attach the cecum to the wall of the abdomen to hold it in place.

References

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

NIDDK would like to thank:

Samantha Hendren, M.D., M.P.H., University of Michigan, and Joseph Levy, M.D., New York University School of Medicine