Cystocele

On this page:

- What is a cystocele?

- Does a cystocele have another name?

- How common is a cystocele?

- Who is more likely to have a cystocele?

- What are the complications of a cystocele?

- What are the symptoms of a cystocele?

- What causes a cystocele?

- How do health care professionals diagnose a cystocele?

- How do health care professionals treat a cystocele?

- Can I prevent a cystocele?

- Clinical Trials for a Cystocele

What is a cystocele?

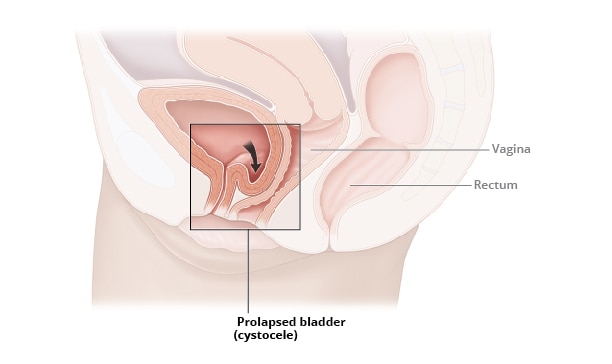

A cystocele is a condition in which supportive tissues around the bladder and vaginal wall weaken and stretch, allowing the bladder and vaginal wall to fall into the vaginal canal.

Usually, the muscles and connective tissues that support the vaginal wall hold the bladder in place. With a cystocele, the muscles and tissues supporting the vagina weaken and stretch, allowing the bladder to move out of place.

A cystocele is the most common type of pelvic organ prolapse. Pelvic organ prolapse occurs when the vaginal walls, uterus, or both lose their normal support and prolapse, or bulge, into the vaginal canal or through the vaginal opening. Other nearby pelvic organs, such as the bladder or bowel, may be involved and also drop from their normal position in the body.

Health care professionals usually rank a cystocele using a grading or staging system. Grade 1 is the mildest form of the condition, and grades 3 and 4 are the most serious. With a more advanced cystocele, your bladder and vaginal wall may drop down far enough that they reach or bulge into the vaginal canal and potentially out through the opening of the vagina.

View full-sized image A cystocele occurs when supportive tissues around the vaginal wall and bladder weaken and stretch, allowing the bladder and vaginal wall to bulge into the vaginal canal.

View full-sized image A cystocele occurs when supportive tissues around the vaginal wall and bladder weaken and stretch, allowing the bladder and vaginal wall to bulge into the vaginal canal.

Does a cystocele have another name?

A cystocele may be called a prolapsed bladder, anterior vaginal wall prolapse, or fallen bladder.

How common is a cystocele?

A cystocele is common. Experts estimate that nearly half of women who have given birth have some degree of pelvic organ prolapse.1 However, many other women with the condition do not have symptoms or do not seek care from a health care professional. As a result, the condition is underdiagnosed, and it is not known exactly how many women are affected by cystoceles.

Who is more likely to have a cystocele?

A cystocele can affect women of any age, but your chances of developing a cystocele increase with age because muscles and tissues often become weaker over time. Other factors that increase your risk of having a cystocele include

- giving birth vaginally

- having a history of pelvic surgery such as a hysterectomy or pelvic organ prolapse repair surgery

- being overweight or having obesity

- having a family history of pelvic organ prolapse

What are the complications of a cystocele?

A cystocele may put pressure on or lead to a kink in the urethra and cause urinary retention, a condition in which you are unable to empty all the urine from your bladder. In rare cases, a cystocele may result in a kink in the ureters and cause urine to build up in the kidney, which can lead to kidney damage.

What are the symptoms of a cystocele?

Many women with cystoceles have no symptoms. The more advanced a cystocele is, the more likely it is you will experience symptoms. Symptoms of a cystocele may include

- a vaginal bulge or the feeling that something is falling out of the vagina

- pressure in the vagina or pelvis

These symptoms may get worse when you strain, lift heavy items, cough, or stand for a long time, and symptoms may get better when you lie down.

Other symptoms may include

- urine leakage, called urinary incontinence

- difficulty starting the flow of urine, called hesitancy

- a slow urine stream

- feeling the need to urinate after finishing urination

- frequent or urgent urination

What causes a cystocele?

Weakened or damaged muscles and connective tissues that support the bladder and vaginal walls cause a cystocele. Multiple factors may contribute to the stretching or weakening of these muscles and tissues, including

- pregnancy and childbirth, particularly vaginal childbirth

- conditions that repeatedly strain or increase pressure in the pelvic area, such as severe constipation, obesity, heavy lifting, or chronic cough

- prior pelvic reconstructive surgeries, such as hysterectomy or pelvic organ prolapse repair surgery

- inherited genes

- certain connective tissue disorders, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

How do health care professionals diagnose a cystocele?

To diagnose a cystocele, health care professionals ask about your symptoms and medical history and perform a physical exam, including a pelvic exam to check your lower abdomen. You may be asked to stand during part of the exam, which may feel awkward but allows your health care professional to determine the severity of your cystocele. Your health care professional may also order medical tests to determine how advanced the cystocele is or to help find or rule out other problems in your urinary tract or pelvis.

Medical history

A health care professional may ask about your

- symptoms, such as bulges or lumps in the vagina, pelvic pressure or heaviness, and urinary incontinence

- pregnancy and childbirth history

- current and past medical problems, including surgeries

- family history

- over-the-counter and prescription medicines

- bowel habits

Medical tests

If you are having trouble completely emptying your bladder or experience other lower urinary tract symptoms, your health care professional may use one or more of the following tests to look at your urinary tract.

- Postvoid residual urine measurement determines how much urine is left in your bladder after urination.

- Voiding cystourethrogram uses x-rays ;to show how urine flows through the bladder and urethra.

Many women have cystoceles. Talk with your health care professional about any symptoms you may have and possible treatments.

Many women have cystoceles. Talk with your health care professional about any symptoms you may have and possible treatments.

How do health care professionals treat a cystocele?

Your cystocele usually does not need treatment if you don’t have symptoms.

If you have a cystocele with symptoms, your health care professional may recommend nonsurgical treatment or surgery, depending on the severity of the cystocele, your age, other health problems, sexual activity, desire for future children, and personal preferences.

Nonsurgical treatments

Your health care professional may suggest

- Pelvic floor exercises. Also called Kegel exercises, these structured, individualized exercises help strengthen pelvic floor muscles. Strong pelvic floor muscles help hold the bladder in place and keep urine from leaking.

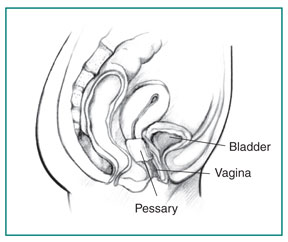

- Vaginal pessary. A pessary is a small silicone device that is inserted into the vagina to support the vaginal wall and hold your bladder in place. Your health care professional will choose from a variety of shapes and sizes of pessaries to find the pessary that is the most comfortable fit for you. Some women use a pessary while waiting for surgical treatment or if they prefer not to have surgery. Pessaries must be removed and cleaned regularly to prevent vaginal irritation. Your health care professional will show you how to clean and reinsert the pessary on your own.

Your health care professional may suggest you use a pessary to help hold your bladder in place and ease your symptoms.

Your health care professional may suggest you use a pessary to help hold your bladder in place and ease your symptoms.

Surgery

Your health care professional may consider surgery to treat a cystocele if nonsurgical treatments don’t work or your cystocele is severe.

The most common surgical procedure to repair a cystocele is anterior vaginal repair, also called anterior colporrhaphy. During this procedure, a surgeon puts the bladder back in its normal position and tightens the muscles and tissues that hold the bladder in place using stiches.

Your health care professional may perform a procedure to treat or prevent urinary incontinence at the same time as the surgery to repair the cystocele.

Another surgical option to treat a cystocele is obliterative surgery, which is a procedure that narrows or closes off all or part of the vagina to provide more support for the bladder. After having this surgery, a woman is no longer able to have vaginal intercourse.

Can I prevent a cystocele?

Usually a cystocele cannot be prevented, but you can take steps to relieve your symptoms and help prevent your cystocele from getting worse.

Do pelvic floor muscle exercises

Strong pelvic floor muscles help hold the pelvic organs in place. Kegel exercises can make the pelvic floor muscles stronger.

Maintain a healthy weight

Being overweight puts pressure on your pelvis. Make changes to your diet and lifestyle, such as eating more fruits and vegetables and getting regular physical activity.

Avoid heavy lifting and lift correctly

When lifting heavy objects, use your legs instead of your waist or back.

Prevent and treat constipation

Get enough fiber in your diet, drink plenty of water and other liquids, and get regular physical activity.

Control chronic cough

Get treatment for a chronic cough or bronchitis and avoid smoking.

Clinical Trials for a Cystocele

The NIDDK conducts and supports clinical trials in many diseases and conditions, including urologic diseases. The trials look to find new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease and improve quality of life.

What are clinical trials for a cystocele?

Clinical trials—and other types of clinical studies—are part of medical research and involve people like you. When you volunteer to take part in a clinical study, you help doctors and researchers learn more about disease and improve health care for people in the future.

Researchers are studying many aspects of a cystocele, such as

- new surgical techniques to correct a cystocele

- ways to reduce complications and improve patient satisfaction after surgery

- the effect of pelvic floor muscle training on women with various stages of pelvic organ prolapse

Find out if clinical studies are right for you.

Watch a video of NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers explaining the importance of participating in clinical trials.

What clinical studies for a cystocele are looking for participants?

You can view a filtered list of clinical studies on cystoceles that are open and recruiting at ClinicalTrials.gov. You can expand or narrow the list to include clinical studies from industry, universities, and individuals; however, the National Institutes of Health does not review these studies and cannot ensure they are safe. Always talk with your health care provider before you participate in a clinical study.

References

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Catherine S. Bradley, M.D., M.S.C.E., University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine